Provided by Cognitive Sciences ePrint Archive

Models of Cognition:

Neurological possibility does not indicate neurological plausibility.

Peter R. Krebs ([email protected])

Cognitive Science Program

School of History & Philosophy of Science

The University of New South Wales

Sydney, NSW 2052, Australia

Abstract

Many activities in Cognitive Science involve complex

computer models and simulations of both theoretical

and real entities. Artificial Intelligence and the study

of artificial neural nets in particular, are seen as ma-

jor contributors in the quest for understanding the hu-

man mind. Computational models serve as objects of

experimentation, and results from these virtual experi-

ments are tacitly included in the framework of empiri-

cal science. Cognitive functions, like learning to speak,

or discovering syntactical structures in language, have

been modeled and these models are the basis for many

claims about human cognitive capacities. Artificial neu-

ral nets (ANNs) have had some successes in the field of

Artificial Intelligence, but the results from experiments

with simple ANNs may have little value in explaining

cognitive functions. The problem seems to be in re-

lating cognitive concepts that belong in the ‘top-down’

approach to models grounded in the ‘bottom-up’ con-

nectionist methodology. Merging the two fundamentally

different paradigms within a single model can obfuscate

what is really modeled. When the tools (simple artifi-

cial neural networks) to solve the problems (explaining

aspects of higher cognitive functions) are mismatched,

models with little value in terms of explaining functions

of the human mind are produced. The ability to learn

functions from data-points makes ANNs very attractive

analytical tools. These tools can be developed into valu-

able models, if the data is adequate and a meaningful

interpretation of the data is possible. The problem is,

that with appropriate data and labels that fit the desired

level of description, almost any function can be modeled.

It is my argument that small networks offer a univer-

sal framework for modeling any conceivable cognitive

theory, so that neurological possibility can be demon-

strated easily with relatively simple models. However, a

model demonstrating the possibility of implementation

of a cognitive function using a distributed methodol-

ogy, does not necessarily add support to any claims or

assumptions that the cognitive function in question, is

neurologically plausible.

Introduction

Several classes of computational model and simulation

(CMS) used in Cognitive Science share common ap-

proaches and methods. One of these classes involves

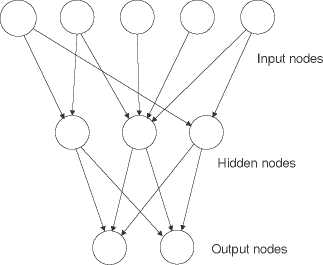

artificial neural nets (ANNs) with small numbers of

nodes, particularly feed forward networks (Fig. 1) and

simple recurrent networks (SRNs)1 (Fig. 2). Both of

these architectures have been employed to model high

1 SRNs have a set of nodes that feed some or all of the

previous states of the hidden nodes back. The nodes are

often described as context nodes. They provide a kind of

level cognitive functions like the detection of syntactic

and semantic features for words (Elman, 1990, 1993),

learning the past tense of English verbs (Rumelhart and

McClelland, 1996), or cognitive development (McLeod

et al., 1998; Schultz, 2003). SRNs have even been

suggested as a suitable platform “toward a cognitive

neurobiology of the moral virtues” (Churchland, 1998).

While some of the models go back a decade or more,

there is still great interest in some of these ‘classics’,

and similar models are still being developed, e.g. Rogers

and McClelland (2004). I argue that many models in

this class explain little at the neurological level about

the theories they are designed to support, however I do

not intend to offer a critique of connectionism following

Fodor and Pylyshyn (1988).

Figure 1. Feed forward network architecture

Instead, this paper concerns models where ANNs act

merely as mathematical, or analytical, tools. The fact

that mathematical functions can be extracted from a

given set of data, and that these functions can be success-

fully approximated by an ANN (neurological possibility),

does not provide any evidence that these functions are

capable of being realized in similar fashion inside human

brains (neurological plausibility).

Bridging the Paradigms

Theories in Cognitive Science fall generally into two dis-

tinct categories. Some theories are offered as explana-

tions of aspects of human cognition in terms of what

‘short term memory’ that becomes part of the input in the

next step of the simulation.

1184

More intriguing information

1. THE ANDEAN PRICE BAND SYSTEM: EFFECTS ON PRICES, PROTECTION AND PRODUCER WELFARE2. Retirement and the Poverty of the Elderly in Portugal

3. Agricultural Policy as a Social Engineering Tool

4. The economic doctrines in the wine trade and wine production sectors: the case of Bastiat and the Port wine sector: 1850-1908

5. The name is absent

6. The name is absent

7. Developmental Robots - A New Paradigm

8. Education and Development: The Issues and the Evidence

9. The name is absent

10. A model-free approach to delta hedging