40

According to the 2001 census, 82 per cent of interprovincial migrants were of

working age (15 and over) and the employment rate of working age migrants was 66 per

cent. This implies that of the 370,791 migrants in 2006, 201 thousands were employed in

the destination province. In 2006, total employment in Canada was 16,484 thousand so

interprovincial migrants represented 1.22 per cent of this total. Labour income, expressed

in current prices, was $737 billion, 53 per cent of GDP. Assuming that the labour income

of migrants is the same as the average worker, labour income for interprovincial migrants

was $9.0 billion. If wages were 4.6 per cent higher for this group due to interprovincial

migration, this gain was $413 million in labour income and $779 million in GDP, the

latter equivalent to 0.05 per cent of GDP.28

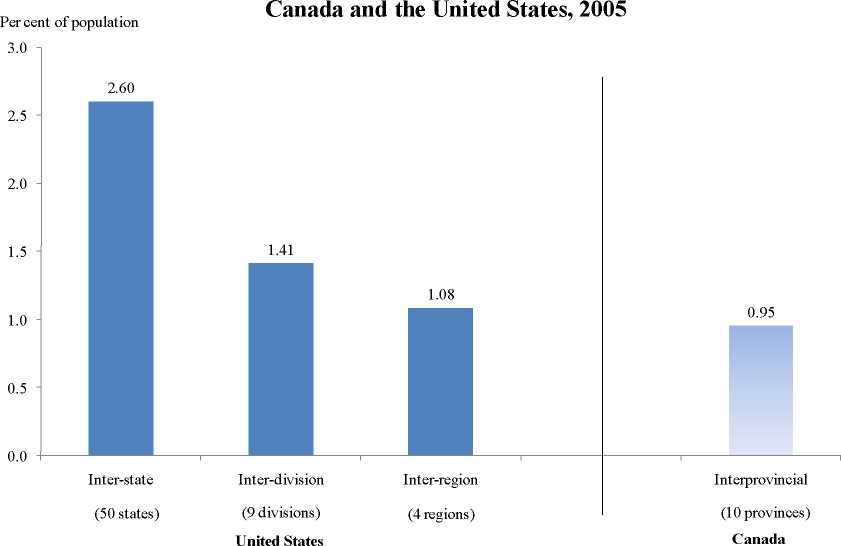

Chart 14: Comparison of One-Year Geographic Labour Mobility in

The second methodology used to estimate the impact of interprovincial migration

on productivity gives larger results as it takes a broader approach to the concept of

productivity, a social productivity perspective. It includes the benefits for the economy

from persons going from non-employment to employment through migration.

Sharpe, Arsenault and Ershov (2007) quantify changes in aggregate output and

labour productivity brought about by the interprovincial migration of workers. Total

output gains are the result of two separate effects, the effect of employment gains as a

result of interprovincial migration and the effect of the re-allocation of workers between

28 This calculation of course ignores the gains from intraprovincial migration, which as noted is three times

as important as interprovincial migration. Therefore the total impact on GDP of both types of migration

may be closer to $240 million

More intriguing information

1. The name is absent2. Towards Teaching a Robot to Count Objects

3. Placentophagia in Nonpregnant Nulliparous Mice: A Genetic Investigation1

4. The constitution and evolution of the stars

5. APPLYING BIOSOLIDS: ISSUES FOR VIRGINIA AGRICULTURE

6. Special and Differential Treatment in the WTO Agricultural Negotiations

7. New Evidence on the Puzzles. Results from Agnostic Identification on Monetary Policy and Exchange Rates.

8. A production model and maintenance planning model for the process industry

9. The voluntary welfare associations in Germany: An overview

10. A Review of Kuhnian and Lakatosian “Explanations” in Economics