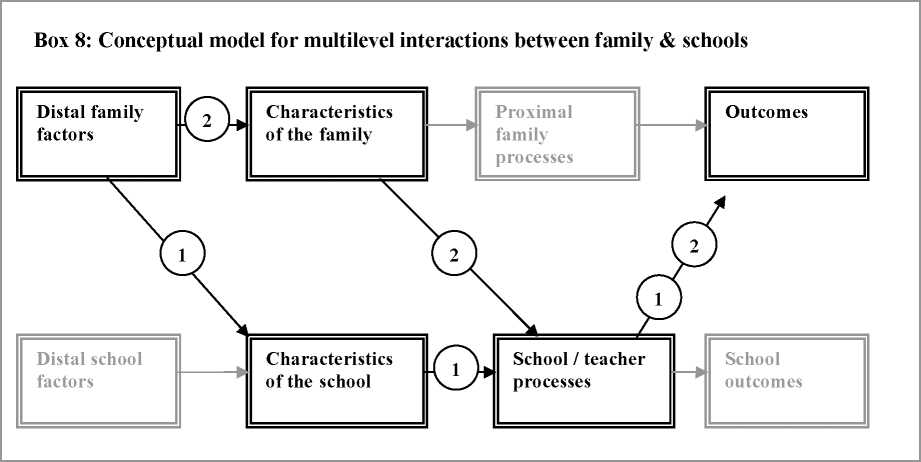

The importance of context

A second channel for the effect of family distal factors is through an impact on the

relationships with teachers and the school (arrows 2). This has been studied mainly in

terms of social class differences (Bernstein, 1990, 1996). In qualitative analysis of

data collected from sociolinguistic experimentation over a series of years with

children from working class and middle class backgrounds, he found that the

language used by classroom teachers, which he termed restricted codes, were

constrained to favour their middle class students over their working class peers.

Comparable problems with language and identity were identified in an ethnographic

case study of a working class teacher in a London Education Action Zone (EAZ)

(Burns, 2001). Her study found that the teacher had to severely restrict her language

and pretend to adopt a middle class culture in order to progress in the school.

It has also been hypothesised that teachers may have higher expectations for middle

class children and so treat them preferentially leading to a relationship between family

background on perceived background and pupil teacher interactions. Similarly, the

cognitions and values of parents are important characteristics of the family context.

Parents bring these characteristics to the interactions they have with their children’s

school. They may, for example, be more proficient in interacting with teachers as well

as better able to support and reinforce traditional academic goals (Hess & Holloway,

1984; Slaughter & Epps, 1987). Similarly, teachers are likely to recognise these

characteristics of children and their parents and may respond more positively to them.

Teachers may come to make assumptions about parents’ cognitions and values from

signals provided by distal elements of social class (parental education, income and

occupational status) or on features of family structure without these necessarily being

mediated by actual family characteristics. These in turn can impact on teacher’s views

of pupils (Mortimore & Blackstone, 1982; Mortimore et al., 1988). These child-

teacher interactions are thus a channel for the effects indicated by arrow 2 in Box 8.

39

More intriguing information

1. Thresholds for Employment and Unemployment - a Spatial Analysis of German Regional Labour Markets 1992-20002. Pursuit of Competitive Advantages for Entrepreneurship: Development of Enterprise as a Learning Organization. International and Russian Experience

3. EMU: some unanswered questions

4. Weather Forecasting for Weather Derivatives

5. MANAGEMENT PRACTICES ON VIRGINIA DAIRY FARMS

6. The name is absent

7. The name is absent

8. FOREIGN AGRICULTURAL SERVICE PROGRAMS AND FOREIGN RELATIONS

9. The name is absent

10. Housing Market in Malaga: An Application of the Hedonic Methodology