Young

Evaluating Social Welfare Effects

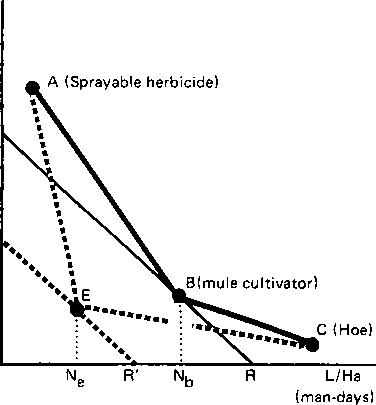

parallel to PR, E becomes the least cost and the

most socially efficient weed control technique.

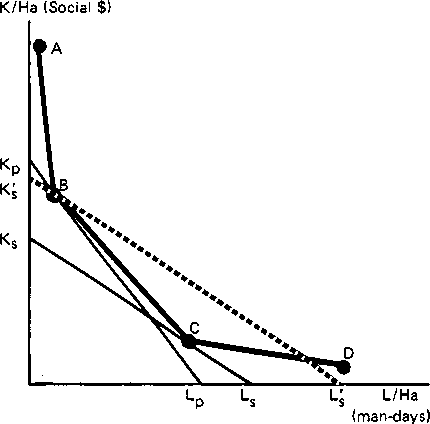

The development of the granular herbicide

generates P-P' dollars per hectare of efficiency

benefits, which represents the reduced resource

cost of producing the same output as before. If

the new technique is adopted over X hectares,

the aggregate short-run benefits would sum to

X(P-P') dollars per year, assuming one crop is

harvested per year. In the short run, these gains

will be captured in the form of Schumpeterian

profits by early adopting farms. Over the long run

they will be translated into increased consumer’s

and/or producer’s surpluses.

This procedure for measuring efficiency bene-

fits is fundamentally identical to that utilized by

Schmitz and Seckler in their evaluation of the

social benefits derived from the introduction of the

mechanical harvester in the processing tomato in-

dustry, although they did not explain the process

within the unit isoquant context. It should be rec-

ognized that these measurements may hold valid

only for the short run, because over the long run

the relative social prices of capital and labor could

change greatly. Schmitz and Seckler projected the

cost savings of the mechanical tomato harvester

through infinity, but this could be a risky practice

in a world of rapidly changing factor prices.

What are the distributional losses caused by the

switch in weed control techniques? Following

Schmitz and Seckier’s approach, the direct costs

borne by displaced hired labor can be measured

by the reduction in the earnings of the relevant

labor force after the change. Theoretically, if the

gains received by “winners” from the efficiency-

enhancing new technology were sufficient to com-

pensate the “losers” for their lost earnings, then all

groups could be made at least as well off after as

before the inovation. In reality, however, such

compensation is rarely paid. Returning to figure 1,

total employment in weed control is reduced by

the quantity (b⅛ - Ne) per hectare. Total earnings

in weed control are reduced proportionately under

the short-run assumption of no change in the price

of labor, Pl. The quantity Pjj (Nb - Ne) per

hectare defines the upper bound on labor’s losses.

On the other hand, if 100 percent of the dis-

placed workers find equal-paying jobs elsewhere,

their short-run losses are zero. Most often, labor’s

losses will lie somewhere between these two

extremes.

The preceding measurements are short-run, and

assume certain inflexibilities in wages and labor

mobility to rationalize the existence of any un-

employment. In a depressed area like the Brazilian

Northeast, resulting unemployment could persist

Fig. 1.

К/Ha (Social $)

Fig. 2.

231

More intriguing information

1. The name is absent2. Rural-Urban Economic Disparities among China’s Elderly

3. The name is absent

4. Innovation and business performance - a provisional multi-regional analysis

5. The name is absent

6. Cross border cooperation –promoter of tourism development

7. Activation of s28-dependent transcription in Escherichia coli by the cyclic AMP receptor protein requires an unusual promoter organization

8. Revisiting The Bell Curve Debate Regarding the Effects of Cognitive Ability on Wages

9. The name is absent

10. Input-Output Analysis, Linear Programming and Modified Multipliers