stringency of regulatory environments; and (4) the rules governing the vitality of

competition and the incentives for productive modes of rivalry (Porter, Sachs &

Warner, 2000). The key point to derive from this analysis is that while such

‘economic business environments’ are not unique to Northern California, they are far

from ubiquitous. Because they rely on massive sums of public funding, as will be

shown, a moral dilemma arises for policy makers alert to regional disparities. Should

they encourage spatial concentration to achieve global excellence or should they

encourage the development of such facilities in less favoured regions too? Keep in

mind that the latter are where negative health imbalance is often as pronounced as

economic weakness in the official statistics. Finally, as health economists and others

are coming to realise, health services and their supporting supply firms in

pharmaceuticals, biotechnology and research laboratories contribute as much as one-

sixth of GDP in some advanced economies (Cassidy, 2002).

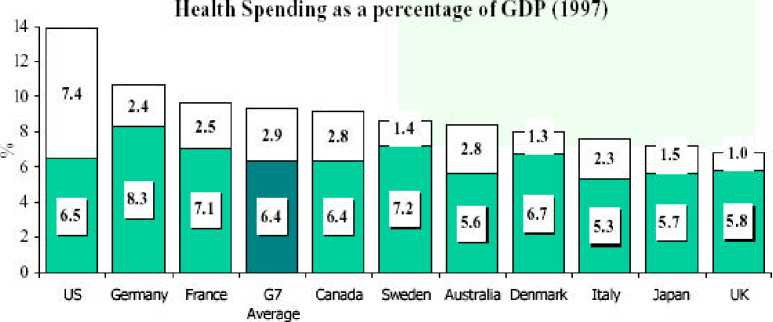

In Table 1 data are presented on public and private health expenditure in a number of

leading OECD countries for 1997. These statistics probably underestimate the whole

■ Public Spending □ Pi ivaie Spending

Source: 2000 OECD Health Data

Table1: Health Expenditure in Leading OECD Countries, 1997

health economy as described above by a few percentage points. Nevertheless they

demonstrate even core health expenditure running at just under 10% for the G7

countries, and much higher, at nearly 14% for the USA.

10

More intriguing information

1. The name is absent2. Can genetic algorithms explain experimental anomalies? An application to common property resources

3. PER UNIT COSTS TO OWN AND OPERATE FARM MACHINERY

4. Do Decision Makers' Debt-risk Attitudes Affect the Agency Costs of Debt?

5. Reversal of Fortune: Macroeconomic Policy, International Finance, and Banking in Japan

6. CONSIDERATIONS CONCERNING THE ROLE OF ACCOUNTING AS INFORMATIONAL SYSTEM AND ASSISTANCE OF DECISION

7. DURABLE CONSUMPTION AS A STATUS GOOD: A STUDY OF NEOCLASSICAL CASES

8. The name is absent

9. The name is absent

10. Credit Market Competition and Capital Regulation