for a socially useful purpose. The Charter outlines the basic doctrine of what is now accepted to be

an appropriate approach to dealing with historic buildings.3

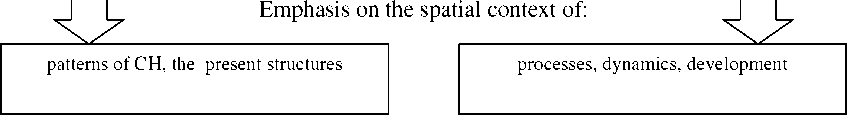

a - CH as an asset to preserve

and promote

MEASUREMENT/PLANNING ACTIVITIES

b - CH and identity as a

resource for development

- Listing of heritage assets

- Development of indicators of existence,

concentration, endangering

- Development of guidelines of heritage

management

- Identification of regional typologies

- Development of indicators of flow (pressure

and development)

- Development of guidelines of spatial

(strategic) planning and cultural policy

TERRITORIAL COMPONENT

Figure 1 Conceptualisation of cultural heritage and operationalisation for the management

of development processes

A fundamental question remains whether heritage is property (“objects”), or a social, intellectual,

and spiritual inheritance. Human actions, our ideas, customs and knowledge, are arguably the most

important aspects of heritage (Harrison, 2005: 1-10). Cultural resource managers seek to understand

and conserve these aspects through work on landscapes, places, structures, artefacts, and archives,

and through work with individuals and the community (Davison 2000; Aplin 2002). Moving from

the field of collection to that of policy and planning, the declaration following UNESCO’s World

Conference on Cultural Policies (Mexico, 1982) states that “... culture consists of all distinctive,

spiritual and material, intellectual and emotional features which characterise a society or social

group”, thus getting closer to the second conceptualisation of heritage as resource.

Another significant subdivision is that between tangible heritage, including cultural assets and

cultural and natural landscapes, and intangible heritage, which focuses on immaterial expressions of

7

More intriguing information

1. Biological Control of Giant Reed (Arundo donax): Economic Aspects2. Strategic Policy Options to Improve Irrigation Water Allocation Efficiency: Analysis on Egypt and Morocco

3. Quelles politiques de développement durable au Mali et à Madagascar ?

4. The name is absent

5. Cross border cooperation –promoter of tourism development

6. The name is absent

7. AN EMPIRICAL INVESTIGATION OF THE PRODUCTION EFFECTS OF ADOPTING GM SEED TECHNOLOGY: THE CASE OF FARMERS IN ARGENTINA

8. Sex-gender-sexuality: how sex, gender, and sexuality constellations are constituted in secondary schools

9. The name is absent

10. The name is absent