14-

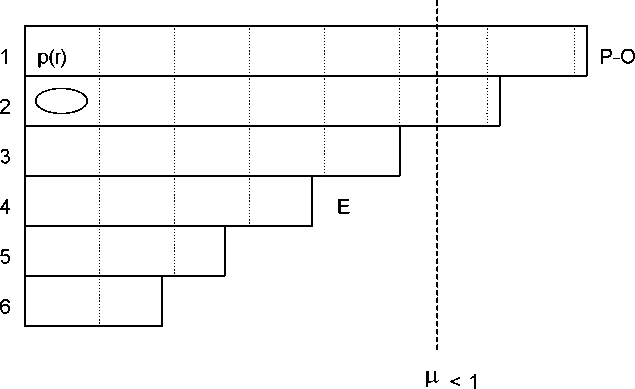

Figure 2: driving on a highway

Two incentives for co-operation can be distinguished:

i) For a given stock of reserves, both parties can co-operate on maintaining constant the

probability of a dictator (keep driving in the same lane). In that way they can avoid increasing

the risk of the system.

ii) Both parties would be better off if they could co-operate in building up reserves in order to

reduce the probability of a take over (moving to a longer lane). But the incumbent will be worse

off if, after building reserves, the opposition party wins the election and consumes part of these

newly built reserves in order to guarantee his re-election. In both cases, in order to sustain co-

operation, the parties may adopt grim strategies that contemplate as a punishment path the

reversion to WE (the stationary lane) as soon as possible.13

However, any level of reserves within the interval [WE, W] (i.e., any of the lanes above the

stationary one) can be a candidate to be selected as the level to be sustained through co-

13 It is assumed, as in the case of the supergame, that this threat is always credible (Friedman 1971). So, if a

deviant incumbent is re-elected, she will not do better than to implement the punishment first. This, however

is a strong assumption because it implies that even after a small deviation has occurred the next incumbent

will be willing to carry the punishment through, which would be a unreasonable thing to do. This problem is

due to the continuity of the pay-off function that contrast with the supergame case. Within the framework

of complete information games this assumption is questionable; a better argument for deterrence against

small changes can be found by allowing some elements of irrationality in the game.

More intriguing information

1. ASSESSMENT OF MARKET RISK IN HOG PRODUCTION USING VALUE-AT-RISK AND EXTREME VALUE THEORY2. The name is absent

3. ALTERNATIVE TRADE POLICIES

4. Growth and Technological Leadership in US Industries: A Spatial Econometric Analysis at the State Level, 1963-1997

5. Computational Experiments with the Fuzzy Love and Romance

6. Party Groups and Policy Positions in the European Parliament

7. The use of formal education in Denmark 1980-1992

8. Popular Conceptions of Nationhood in Old and New European

9. The name is absent

10. The Formation of Wenzhou Footwear Clusters: How Were the Entry Barriers Overcome?