the fourth and second animats approaching to a prey, he imitates their behaviour, and

approaches the second animat. So, what occurred was that the first approached the second and

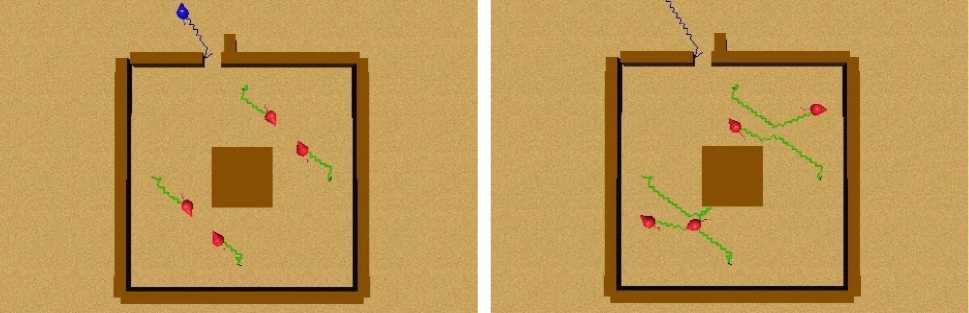

vice versa, and the third approached the fourth and vice versa, as seen in Figure 55. When they

collided, they avoided each other, so the misbelief was broken, and everyone began to explore,

as shown by Figure 56.

Figure 55. Collective misbelief begins. Figure 56. Collective misbelief was broken.

We thought about an experiment where the collective misbelief would not be broken,

or at least not as easily as in the experiments just presented above, but none of our attempts

were successful. Surprisingly, the situation was given by itself, when we were performing an

experiment on the modification of the -’s in a scarce environment. This unexpected result (as

others we have had, such as the emergence of a “nesting” behaviour) was possible because of

the complexity of the BVL and its components: BeCA and I&I.

We observed the behaviours and internal variables of the animats, and concluded the

following: At least one animat conditioned a red spot with grass. He had fatigue, so he

approached a red spot, but without any grass nearby. Without sociality, there would be an

extinction of the conditioning, but another animat with fatigue perceived the first one

approaching grass (the red spot), and he approached him. The fact that both animats were

perceiving each other approaching grass, made them, not only not to lose the conditioning, but

even reinforce it. Another animat with fatigue could fall also in the misbelief. When they

collided with each other, they moved away from the red spot, but since they remembered its

location, they returned again and again. So, they were moving around the red spot, with the

imitation and induction of the other animats keeping them in the area, as seen in Figure 57. We

then put two more animats with fatigue in the vicinity, and they easily fell in the misbelief, as

seen in Figure 58.

87

More intriguing information

1. The name is absent2. The name is absent

3. PROTECTING CONTRACT GROWERS OF BROILER CHICKEN INDUSTRY

4. Innovation Policy and the Economy, Volume 11

5. Creating a 2000 IES-LFS Database in Stata

6. Examining the Regional Aspect of Foreign Direct Investment to Developing Countries

7. DEVELOPING COLLABORATION IN RURAL POLICY: LESSONS FROM A STATE RURAL DEVELOPMENT COUNCIL

8. National urban policy responses in the European Union: Towards a European urban policy?

9. Activation of s28-dependent transcription in Escherichia coli by the cyclic AMP receptor protein requires an unusual promoter organization

10. Literary criticism as such can perhaps be called the art of rereading.