is done while knowing what the impor-

tant things in the image are. Edges,

movement, and other “eye catching”

things tell the visual system where to

look. Once this phase of detection and

deconstruction is done, the visual sys-

tem can refit to the particular image it is

dealing with and can associate it to the

current context. This gives the stimulus

meaning and achieves a functional im-

age, while widening the knowledge of

the visual world via memory.

The fact that our visual ability is

based on and inseparable from our per-

ception of the general properties of vi-

sual stimuli can easily be seen in the

kinds of illusions that fool us. Movies,

animation, and paintings are all only

good copies of natural images in the

sense that they capture the general

properties of the visual world.

Note the different scales involved in

the two phases that we have discussed

so far regarding vision. The first stage,

the stage of priming and obtaining the

achieved set, is a stage that responds to

some external input, but does so in a

duration orders of magnitude longer

than the time needed to process new

input once the system is fully func-

tional. Moreover, the second stage, spe-

cific interaction, is a continuous pro-

cess going on all the time, whereas the

first stage is a once in a lifetime oppor-

tunity. It takes a long time to put to-

gether an organism, but, once it exists,

the organism has to use its mechanisms

immediately.

One cognitive system where this

separation in time is clearly seen

is in the development of language

in children. As infants and children, we

learn to speak, and it is a long and la-

borious process. However, once lan-

guage is acquired, when we add new

words to our vocabulary, learning them

and their correct use is something that

we can do almost instantaneously. We

will deal with only one aspect of the ac-

quisition of language—the learning of

correct syntactic combinations—how

we know the correct order of words that

make a meaningful sentence. This step

is made possible by the previous stages

of auditory and cognitive development,

which are influenced by various innate

and learned biases. The exact amount

of learned and innate influence is the

scene of many an argument in the cog-

nitive sciences that we will not go into

[7]. In any case, it is obvious that at the

stage of syntactic development the lan-

guage system already has a “tendency”

that sets the stage for the learning of

syntactic combination. This can be seen

in the fact that the learning of sentence

formation is always preceded, in chil-

dren, by a stage of rapid growth in vo-

cabulary or “vocabulary explosion,”

that brings about the creation of the vo-

cabulary necessary for syntactic combi-

nations [8].

In studies concerning the use of in-

transitive and transitive verbs in syntac-

tic combinations, in parents’ conversa-

tions with their children, it was seen

that parents use a very small subset of

verbs at a very high frequency when

talking to their children. Words such as

want, come, go, and make account for

a high fraction of the verbs used in

parental conversation. All these high-

frequency verbs are very general, have

uses that are almost empty semanti-

cally, and can be said to be generic of

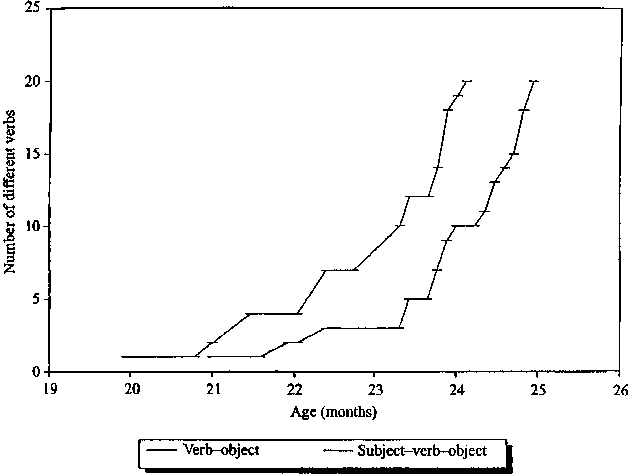

FIGURE 3

the verb subcategories to which they

belong. In return, all the first verbs used

by children are drawn from this group

of verbs (though individually each

child’s first verb need not be the most

commonly said word of his parent).

Further, once the first verbs are learned

in a certain syntactic construction, the

speed of learning other verbs in the

same syntactic construction, but not

necessarily in other constructions, is

greatly enhanced. This could be indica-

tive of a scenario where the child learns

the first 2 or 3 examples, after which the

others are greatly facilitated (Reference

9 and Figure 3).

Figure 3. Cumulative number of different verbs in VO and SVO word combinations produced by

a subject as a function of age [9].

In effect, because of the shape space

of languages, in the course of normal

conversation, children are exposed to

the useful example of the different types

of syntactic combinations and the cor-

rect use of language. The first words are

very common and have many uses (they

embody various ideas). In this fashion

the useful examples of language are cor-

roborated, bringing about the forma-

tion of an achieved set of representa-

tions that greatly facilitates the latter

identification of similarities to the use-

© 2001 John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

CO M PLEXITY

17

More intriguing information

1. The name is absent2. The name is absent

3. TLRP: academic challenges for moral purposes

4. A methodological approach in order to support decision-makers when defining Mobility and Transportation Politics

5. The name is absent

6. Philosophical Perspectives on Trustworthiness and Open-mindedness as Professional Virtues for the Practice of Nursing: Implications for he Moral Education of Nurses

7. The Impact of EU Accession in Romania: An Analysis of Regional Development Policy Effects by a Multiregional I-O Model

8. Macroeconomic Interdependence in a Two-Country DSGE Model under Diverging Interest-Rate Rules

9. EDUCATIONAL ACTIVITIES IN TENNESSEE ON WATER USE AND CONTROL - AGRICULTURAL PHASES

10. The name is absent