the clay in the backward phase, there is a delay between

the torso and arms. The motion consists of two parts

with phase relationship, forming a single cycle with two

modes. We think that this phase relationship is acquired

at the final stage of skill acquisition, following the estab-

lishment of coordination. We discuss below this issue

based on our experimental results.

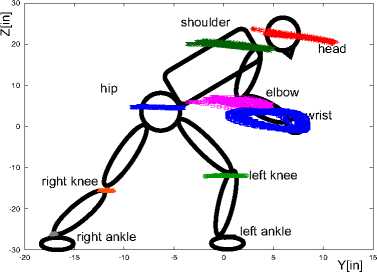

Figure 2: trajectories of kneading (subject A) on the sagittal

plane

right knee

left hip

right hip

30 30.5 31 31.5 32 32.5 33 33.5 34

Time[s]

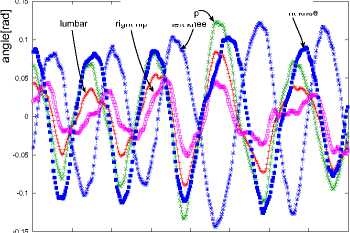

Figure 3: time series of subject A (expert)

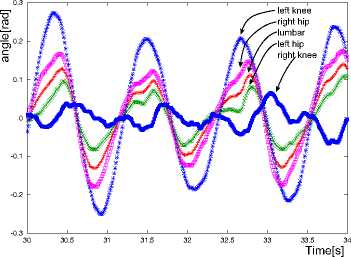

Figure 4: time series of subject B (experienced)

4.2 differentiation within coordination in

kneading

As previously reported (Abe et al., 2003), we found the

trajectories to be well coordinated as a person gets more

experienced in the task. While only a qualitative anal-

ysis was presented in our previous work, we present in

this paper a quantitative analysis of the coordination.

Let us begin with a description of coordination. In our

experiment, the localisation of trajectories are found for

both the experienced persons and experts (i.e., subjects

A, B, C and D). Although we previously found an ex-

pert’s trajectory to be highly localised, the experts who

took part in the current experiment did not show such

strong localisation. Contrarily, the experienced persons

(subject B and C) showed better localisation as long as

trajectories in the real space is concerned.

Figures 3 and 4 depict the time series of subject A and

B, respectively. The latter may give better impression

of strong synchronisation. Applying FFT (Fast Fourier

Transformation), we found that subject B’s motion has

sharper peaks for all angles while subject A’s has a single

broader peak. Then if we only consider the strength of

synchronisation, subject A is regarded to be inferior to

B.

Subject A is, however, more skillful than the others as

long as we judge their skills based on their end products.

It is important to note that the establishment of coordi-

nation is merely halfway to skill acquisition as described

below.

Next, we turn to analysis of differentiation. In the

present work, we evaluated the relative phases among

joints and confirmed our previous findings.

In Figures 5 to 7, the histograms of relative phase are

shown for subjects A, B and C, respectively. The refer-

ence angle was chosen to be the hip of anterior stance

side, i.e., left hip. Data are extracted from a single trial,

but qualitative features are preserved.

For all the subjects except E (i.e., novice), a synchro-

nisation is observed between the reference angle and the

lumbar. The other hip is almost synchronising although

a small delay was found in subject A.

In the torso, we do not find any synchronisation of the

neck. This may be due to that reduction of our body

model (i.e., the chest and top of the neck). Especially,

the movement of viewpoint affects the attitude of the

head (i.e., top of the neck) and we expect a coordination

to be observed if we have adopted a more detailed body

model.

The movement of arm is most important part of the

motion because only the hands touch the clay physically.

As noted, one possibility for the efficient way of knead-

ing is to use the gravitational force to help to press the

clay down. This pattern is found among the experienced

persons. In Figures 6 and 7, the arm is synchronising

(subject C) or proceeding (sub ject B) to the hip. They

tended to push the clay with the help of momentum of

the whole body. By stretching the elbow prior to swing

down of the body, the arms become stiff and easily press

the clay to stretch it out. A disadvantage of this move-

ment is that the rest of a cycle is only to swing back the

100

More intriguing information

1. The name is absent2. FOREIGN AGRICULTURAL SERVICE PROGRAMS AND FOREIGN RELATIONS

3. The name is absent

4. ENERGY-RELATED INPUT DEMAND BY CROP PRODUCERS

5. Conflict and Uncertainty: A Dynamic Approach

6. The name is absent

7. The name is absent

8. The name is absent

9. The name is absent

10. Beyond Networks? A brief response to ‘Which networks matter in education governance?’