fication proved to be a much more sensitive test for

detecting category effects (albeit all living deficits) than

picture naming or naming-to-description (although

there were also differences across pathologies). This

suggests that the direction of category effects some-

times seems to depend upon which test is chosen as the

reference test (a prospect that has not been previously

entertained). In this context, it is worth noting that pa-

tients who show living disorders tend to be agnosic, and

therefore, tested with picture naming; however, sev-

eral nonliving cases have been aphasic, and thus, were

not tested with picture naming, but with tasks such

as picture-name matching (see Laws, 2004). Hence, it

is common for different category effects to rely upon

different testing procedures; and as such, again the

existing literature may be prone to some of the issues

raised here.

Dissociations and Paradoxical Dissociations

Dissociations often form the basis for speculations about

cognitive architecture and modularity especially when

they are doubly dissociated between patients. The cur-

rent study shows, however, that dissociations can occur

within a patient. Within-patient double dissociations

across tasks (e.g., a living on Task A and a nonliving

on Task B) that are believed to have some critical

processing stage in common, raise questions about the

double-dissociation methodology in single-case studies

and the interpretation of category effects per se. At a

theoretical level, many models assume that deficits in

semantics will have ‘‘knock-on’’ effects for naming; and

so, such models have difficulty accounting for paradox-

ical dissociations at the level of semantics and naming.

Paradoxical double dissociations pose problems for

double dissociations at a variety of levels of compari-

son including: across tasks (as described here), within

tasks, and patients (Laws, Gale, et al., 2005); and of

course, across patients and across tasks (the typical

approach in category specificity and cognitive neuro-

psychology more generally). Given that paradoxical

dissociations arise, how might we distinguish a paradox-

ical dissociation from a real double dissociation (i.e.,

one that might be used to ground theories of cognition

or ‘‘carve cognition at its modular joints’’)?

How should paradoxical dissociations be interpreted?

Of course, it might be argued that paradoxical dissocia-

tions are simply unreliable. Indeed, because we did not

retest patients, we have no way of confirming whether

paradoxical dissociations are reliable. Nonetheless, the

reliability of paradoxical dissociations has to be viewed

alongside the fact that reliability is hardly ever examined

for dissociations in single-case studies. Indeed, follow-up

analyses of the same patient by same or other research

groups are rare and sometimes contradictory (Laws,

1998). Hence, it is crucial for future studies to examine

the reliability of all dissociations.

We must also consider the possibility that paradoxical

double dissociations ref lect confounding variables. It

might be argued, for example, that f luctuations in

attention could impact differentially over the test session

and potentially affect one category more than the other.

This is unlikely because it would require that the

confound interacts highly selectively with category. Liv-

ing and nonliving stimuli (on all tests) were randomly

intermixed when presented, so a factor such as attention

f luctuation would have to impact only when items from

one of the two categories were presented. This seems

even more implausible in cases when we consider

paradoxical dissociations (i.e., in the opposite direction

on a second test). Consider the case of the HSE patient

MF (see Figure 1), who showed a classical double

dissociation across tasks. His picture naming was below

the 1% for living things (and normal for nonliving

things); and below the 1% for nonliving on feature

verification (but normal for living things). In this con-

text, we would argue that the dissociations are robust to

any artifacts of this kind.

Another potential confound concerns the possibility

that the dissociations reported here (whether consistent

or paradoxical) are chance findings emerging from quite

noisy patient data, and that multiple analyses might

increase the likelihood of spurious outcomes. Indeed,

typical statistical/methodological approaches may well

be prone to producing spurious and chance findings in

case study analyses. Nevertheless, Monte Carlo simula-

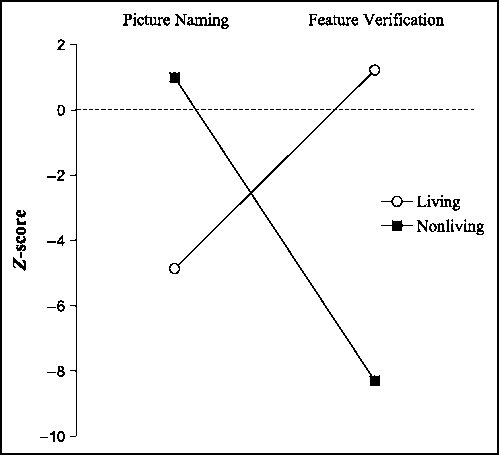

Figure 1. A classical paradoxical double dissociation between living

and nonliving things within one HSE patient (MF). Note: Patient MF

displays a classical double dissociation across category (i.e., impaired

picture naming for living things, but normal nonliving thing naming).

On feature verification, he shows normal living and impaired nonliving

performance. Classical double dissociations (often with weaker

evidence than here) typically provide the strongest evidence for the

separation of cognitive processed (or architecture).

Laws and Sartori 1457

More intriguing information

1. Macroeconomic Interdependence in a Two-Country DSGE Model under Diverging Interest-Rate Rules2. Poverty transition through targeted programme: the case of Bangladesh Poultry Model

3. Optimal Tax Policy when Firms are Internationally Mobile

4. Momentum in Australian Stock Returns: An Update

5. Demographic Features, Beliefs And Socio-Psychological Impact Of Acne Vulgaris Among Its Sufferers In Two Towns In Nigeria

6. Computational Batik Motif Generation Innovation of Traditi onal Heritage by Fracta l Computation

7. Studies on association of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi with gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus and its effect on improvement of sorghum bicolor (L.)

8. Estimating the Impact of Medication on Diabetics' Diet and Lifestyle Choices

9. A parametric approach to the estimation of cointegration vectors in panel data

10. BODY LANGUAGE IS OF PARTICULAR IMPORTANCE IN LARGE GROUPS