93

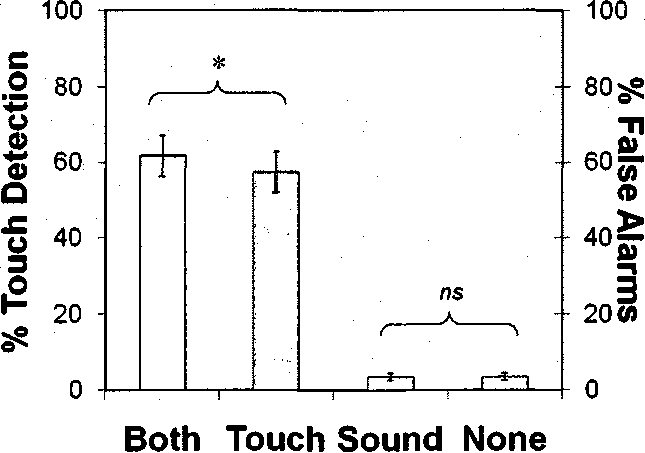

alone could not reliably produce a somatosensory percept. However, there was a

significant interaction between the auditory stimulus and somatosensory stimulus

factors (F1,ιg = 6.69, p = .02), showing that sound can modulate somatosensory

perception. As shown in Figure 1 and Table 1, this interaction was due to a significant

increase in the detection rate for somatosensory stimuli when they were accompanied

by an auditory stimulus (61.6% vs. 57.4%; tιg = 2.121, p = .047). Importantly, although

the sound increased the detection rate when a somatosensory stimulus was presented,

the sound did not increase the false alarm rate for reporting a somatosensory stimulus

when none was presented (3.4% for sound present vs. 3.4% for sound absent; F < 1).

This shows that increase in the detection rate for somatosensory stimuli with sounds

was not due to confounding factors, such as feeling mechanical vibrations or air

pressure from the speakers.

Figure 1. The data from Experiment 1 examining the effects of audition on touch perception.

The left half of the figure shows the hit rates, whereas the right half of the figure illustrates

the false alarm rates. Error bars reflect ±1 standard error of the mean.

More intriguing information

1. Labour Market Flexibility and Regional Unemployment Rate Dynamics: Spain (1980-1995)2. The name is absent

3. Optimal Tax Policy when Firms are Internationally Mobile

4. Estimating the Impact of Medication on Diabetics' Diet and Lifestyle Choices

5. The name is absent

6. How Offshoring Can Affect the Industries’ Skill Composition

7. The name is absent

8. FUTURE TRADE RESEARCH AREAS THAT MATTER TO DEVELOPING COUNTRY POLICYMAKERS

9. The Impact of Individual Investment Behavior for Retirement Welfare: Evidence from the United States and Germany

10. FOREIGN AGRICULTURAL SERVICE PROGRAMS AND FOREIGN RELATIONS