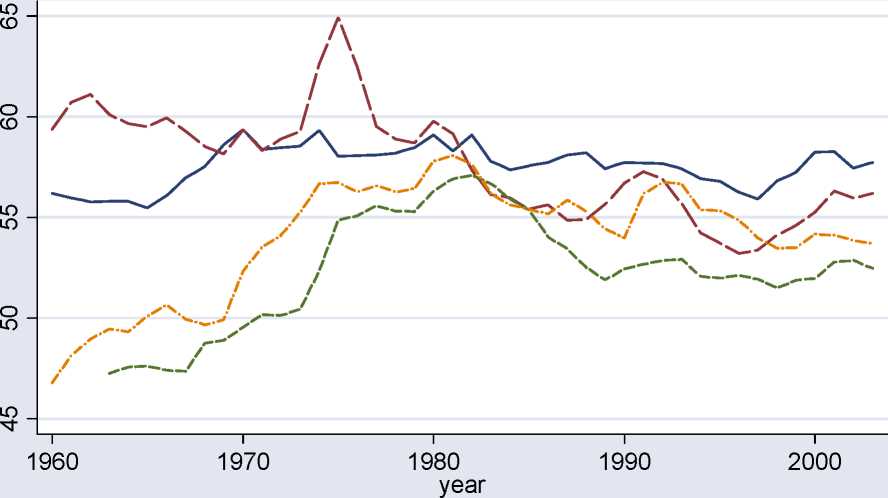

Figure 1 — Compensation of employees over GDP — 1960-2003

labour shares-compensation per employees/value added

----- USA ---UK

------- FRANCE ---------- GERMANY

We start by presenting the theoretical framework. First, we consider how labour market outcomes

—that is, the relative wage, the labour share and the unemployment rate- are determined in an economy

with non-competitive labour markets. Crucially for our purposes, we suppose the aggregate production

function is CES, implying that the labour share is not constant but rather depends on factor inputs. Since

labour markets are not competitive, labour market institutions, by affecting employment levels, become an

essential determinant of the labour share. We capture this idea with a model with two types of workers.

Skilled workers are subject to efficiency wage considerations, which imply no market clearing. For the

unskilled the wage and employment determination process is the outcome of wage bargaining between a

union that represents unskilled workers and a firm in a right-to-manage framework. We find that the

equilibrium employment levels are a function of union bargaining power, the unemployment benefit, and

the capital-labour ratio. The bargained levels of employment and wages will in turn determine the overall

labour share, wage ratio, and unemployment rate, making them a function of labour market institutions.

The second step is to decompose the Gini coefficient of the distribution of personal incomes in

a model economy. Our highly stylised set up considers four types of agents. The first are the jobless who

receive the unemployment benefit. The second are unskilled workers who receive the unskilled wage.

Lastly, there are skilled workers, which may own capital or not. Those who do not will simply receive the

skilled wage, while those who do (the worker-capitalists) receive both the skilled wage and profits. There

More intriguing information

1. Categorial Grammar and Discourse2. Innovation Policy and the Economy, Volume 11

3. The name is absent

4. Les freins culturels à l'adoption des IFRS en Europe : une analyse du cas français

5. DURABLE CONSUMPTION AS A STATUS GOOD: A STUDY OF NEOCLASSICAL CASES

6. The name is absent

7. Monetary Discretion, Pricing Complementarity and Dynamic Multiple Equilibria

8. Dual Track Reforms: With and Without Losers

9. Reform of the EU Sugar Regime: Impacts on Sugar Production in Ireland

10. The name is absent