his government office may, therefore, be many

kilometers away. Dusuns are represented in the desa

government through their local leaders (kepala dusun).

Through the issuing of Law No. 5, 1974, provincial

government structures throughout Indonesia were

redesigned following the above national model. The

same was done for village governments under Law No.

5, 1979. In the implementation of the latter law,

traditional political structures in the villages were

abolished. The country was thereby divided into uniform

hierarchical units which, at a local level, reflected social

structures in Java, but did not accommodate the

traditional structures in other parts of the country. The

new, uniform structures would, in theory, encourage

similar development of the outer regions of Indonesia.

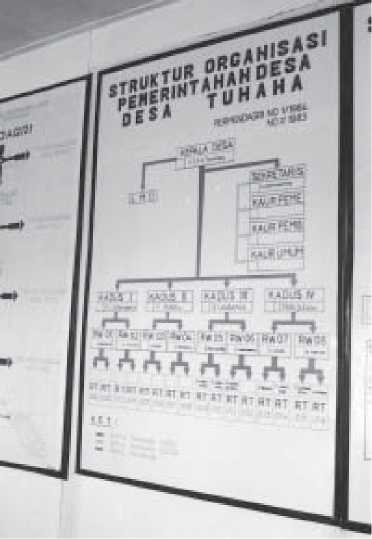

Figure 4.1. (Photo) The village

government structure at Tuhaha.

Through the 1979 law, the hereditary raja was replaced by

an elected village head, the kepala desa. Smaller villages

lost their independent status and became dusuns of larger

desas. The village councils were replaced by bodies known

as the LMD and LKMD (see below). There was no place

in the new structure for the kewang, nor was any

replacement developed to take over the function of resource management. The clan system also

became dysfunctional when, instead of being divided along clan lines, the village territory was

geographically divided into dusuns (hamlets). Dusuns were further divided into RWs (rukun warga:

rukun is a harmonious unit, warga is a society member), and subsequently into RTs (rukun tetangga:

tetangga is neighbor). The RT is the smallest political unit in the village (see Figure 4.1). A small

village like Nolloth, for example, with approximately 2,500 inhabitants, has 16 RTs.

The LMD (Lembaga Masyarakat Desa) is the formal village legislative body occupied with

decision-making and the development of regulations. It has 10 to 15 members presided over

by the village head and the village secretary and is divided into sections, i.e., village

development, government administration and community affairs, each of which has a chief.

The LMD reports to the sub-district government level. The decisions and regulations of the

LMD are executed by the LKMD, which is the administrative body of the village government.

At village meetings, the LKMD members and other government officials make the decisions.

The women sit behind the men and are not involved.

Officially, the villagers elect the LMD members, but as we found out from our interviews, in

many cases LMD members are selected from among traditional authorities (i.e., adat and clan

leaders). Only in a few villages are “commoners” allowed into the LMD. Thus, membership

is more likely to be defined by descent and traditional authority than by local elections. The

extent to which the current government overlaps with the previous, traditional village council

varies, but there was no village where traditional authorities were not represented at all.

Heads of the dusun are usually appointed by the village head (kepala desa) and are acknowledged

through a decree from the sub-district office. The dusun level has no LMD of its own, but dusun

representatives hold positions in the LMD of the desa. The dusun head supervises and coordinates

social organizations and carries out the development programs for the dusun. People are not formally

consulted about these programs, so the dusun head has to know the village priorities very well.

38 An Institutional Analysis of Sasi Laut in Maluku, Indonesia

More intriguing information

1. Ein pragmatisierter Kalkul des naturlichen Schlieβens nebst Metatheorie2. The Structure Performance Hypothesis and The Efficient Structure Performance Hypothesis-Revisited: The Case of Agribusiness Commodity and Food Products Truck Carriers in the South

3. The name is absent

4. Getting the practical teaching element right: A guide for literacy, numeracy and ESOL teacher educators

5. DIVERSITY OF RURAL PLACES - TEXAS

6. Optimal Tax Policy when Firms are Internationally Mobile

7. The name is absent

8. Do Decision Makers' Debt-risk Attitudes Affect the Agency Costs of Debt?

9. BEN CHOI & YANBING CHEN

10. POWER LAW SIGNATURE IN INDONESIAN LEGISLATIVE ELECTION 1999-2004