articles

eggs were then incubated on different

test substrate materials. A bird’s feather

was used to spread the eggs evenly on

the substrates in bunches of 600-1 200

eggs. The natural substrates tested were

roots of Nile cabbage (Pistia stratiotes),

water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes), pond

weed (Ceratophyllum dermasum) and green

grass (Commelina sp.) leaves. The artificial

substrates tested were kakaban mats,

sisal mats, papyrus mats and nylon mats,

all with an equal surface area of

1 350 cm2. Concrete slabs were used

as the control as they are widely used

as a hatching medium in Kenya. All the

test substrates were put in flow-through

concrete troughs. Water temperature

was maintained at 22.9 ±1.1 °C, D.O.

at 5.9 ± 0.2 mgl-1, pH at 7.0 ± 0.5 and

conductivity at 648 ± 10.2 μs throughout

the period of the experiment. The

percentage of hatching was obtained by

using the formula as stipulated in Viveen

et al. (1985). The cost of using each of

the hatching substrates was assessed by

accounting for all expenses incurred for

each of the methods assessed. Completely

Randomized Block Design (CRBD) was

used to allocate 600-1 200 eggs into each

of the experimental units.

The resulting hatching rates were

analyzed by two-way analysis of variance

(ANOVA). Multiple comparison analysis

was used to assess any heterogeneity.

The Multiple Range Test was used to

discriminate among means (Zar 1984).

The tests were at the 95% significance

level (p<0.05). The two-way ANOVA was

also carried out to assess for differences

between the hatching rates of eggs from

different female spawners.

Results

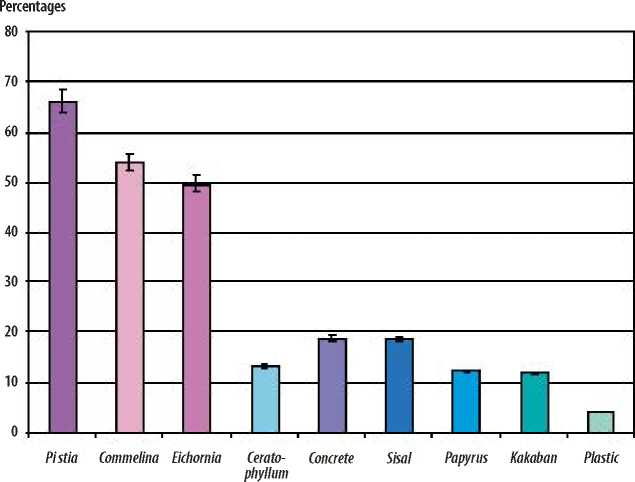

The hatching rates of the eggs on natural

substrates were significantly higher than

on the artificial ones. The mean rates were

66.2, 54.0, 49.7 and 13.0% for Pistia, green

grass leaves (Commelina sp.), E. crassipes

and C. dermasum, respectively (Figure 1).

The difference between the means of

the four data samples was statistically

significant at the 95% confidence level.

Substrates

Figure 1. The percentage hatching rates using different test substrates.

The multiple range tests revealed that

all the means were significantly different

from each other except for one pair - the

difference between green grass leaves and

water hyacinth roots was insignificant.

Three groups of means were identified,

with C. dermasum performing between

15-18%, the green grass leaves (Commelina

sp.) and E. crassipes roots rates falling

between 43-60%, and the Pistia rates

ranking the highest at between 62-76%.

The difference between the means of

the hatching rates of all the artificial test

substrates was also statistically significant.

The hatching rates of the eggs on this

category of substrates were generally low,

with the highest being 18.6% for both the

concrete slabs (control) and sisal mats.

The other mean rates were 4.0, 11.8, and

12.2 for nylon, kakaban, and papyrus mats,

respectively (Figure1). The difference

between the means of the four data

samples was also statistically significant

at the 95% confidence level.

Multiple range tests revealed that all the

means for the artificial substrates were

statistically different from each other.

However, for two pairs of means - the

concrete slab and sisal mats; and kakaban

and papyrus mats - the difference within

each pair was insignificant. Three groups

of means were identified in ranking the

substrates performance. Nylon performed

below 8% and was ranked the lowest,

kakaban and papyrus mats performed

between 8-16%, while sisal mats and

concrete slab performed between 15-25%

and were ranked in the highest group.

There was a significant cost difference

between the use of the artificial

substrates and the natural substrates.

The cost of using the artificial substrates

was higher than for the natural ones.

The cost ranged between US$ 0.12-0.27

for artificial substrates and US$ 0.01-0.03

for natural substrates (Table 1). Direct

costs accounted for much of the cost

incurred in the use of artificial materials,

in contrast to the indirect costs incurred

in the use of the natural materials. The

indirect cost was the opportunity cost

of the man-hours spent in collecting the

substrate materials.

Discussion

The results indicate that the natural

substrates performed better than the

artificial substrates. This was probably

24 NAGA, WorldFish Center Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 3 & 4 Jul-Dec 2005

More intriguing information

1. A novel selective 11b-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 inhibitor prevents human adipogenesis2. Fighting windmills? EU industrial interests and global climate negotiations

3. Behavior-Based Early Language Development on a Humanoid Robot

4. Micro-strategies of Contextualization Cross-national Transfer of Socially Responsible Investment

5. The name is absent

6. A Hybrid Neural Network and Virtual Reality System for Spatial Language Processing

7. The name is absent

8. The technological mediation of mathematics and its learning

9. Second Order Filter Distribution Approximations for Financial Time Series with Extreme Outlier

10. The name is absent