of Natural Resources (funded by the

World Wildlife Fund for Nature), did a

series of studies to assess the impact of

the eruption on marine life and mangrove

communities.

The UPMSI report by Mr. Michael

Atrigenio, Dr. Porfirio Alifio of the UPMSI

and Mr. Ricardo Bifla of the National

Mapping and Resource Information

Authority (NAMRIA)1 pointed out where

reef areas in the Zambales coast are

predominantly affected. Using pre-emption

coral reef data from UPMSI and Haribon

in the area, the group compared estimates

of reef cover and of suspended sediment

concentration on reefs, and how these

affected water turbidity along the ashfall

area and in waters where volcanic ashes

and lahar flowed through the rivers.

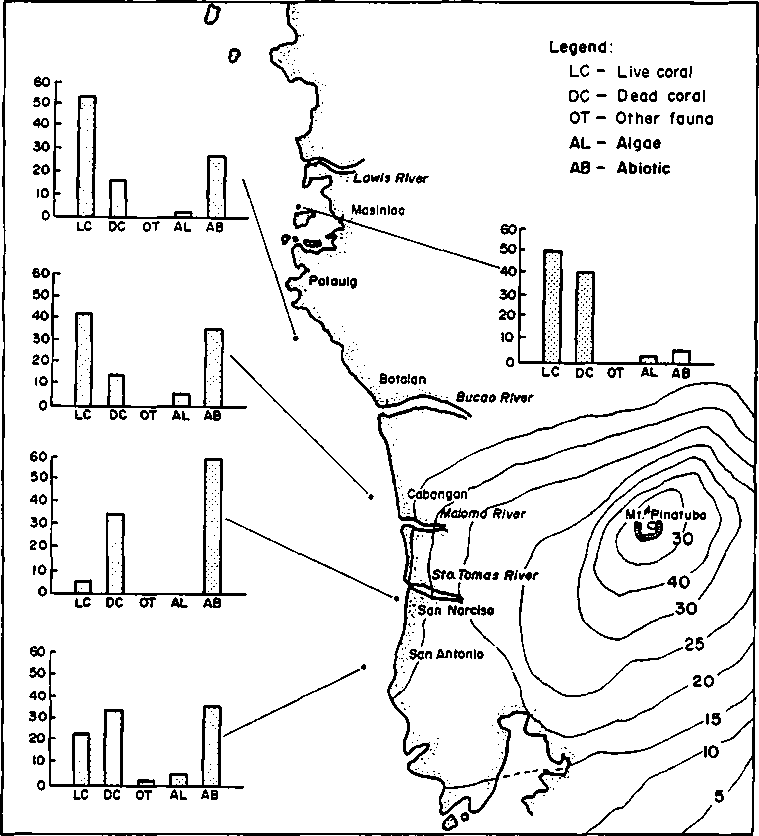

Fig. 3. Mudflow map (shaded), Isopach line for ashfall deposit (cm) and location of

transects and life-form category totals. (Compiled from the data of M.P. Atrigenlo,

P. AUΛo and ft. Blha)

The satellite image obtained by

Atrigenio et al. (Fig. 2) of the Zambales

coast shows very turbid waters spanning

3 km from the coast and relatively turbid

waters extending up to 10 km. The image

shows a northward water current due to

the southwesterly monsoonal winds which

blow from May to November. This means

that the volcanic materials during this

period tend to flow north rather than

toward the southern part of Zambales.

Dead coral cover is high where water

has become turbid, and where volcanic

sediments have concentrated (Fig. 3).

There is also a high percentage of dead

corals in areas far from Pinatubo, related

to other causes such as the usual Siltation

from nearby rivers.

It can be deduced from Fig. 3 that

most of the suspended sediment comes

from the MaIoma and Sto. Tomas rivers

and was spreading northward to settle

on this area’s reefs. However, when the

monsoonal winds change direction, it is

likely that nearby reefs in the southern

area will also be affected. The group

expressed the need for a long-term

monitoring strategy to be able to respond

effectively to the changing scenarios in

these coastal areas.

Effects on

Coral Reef Fishes

With degraded coral reefs, what is

left for fish communities dependent on

them? This is answered in a study done

by Messrs. DomingoOchavillo andHomer

Hernandez and Dr. Aliflo. Their report3

is on fish and coral censuses of five sites

along the coast of Zambales.

Their results show that there is a

decline of fish biomass (Fig. 4) in coastal

areas which received ashfall, with the

decline becoming greater as ash deposits

increase. Coral cover and fish biomass

increased with decreasing ash deposits.

Fish biomass decline may have been

due to mortality from ashfall deposit,

starvation due to loss of food caused by

thedeeɪineof prey abundance (alsocovered

by ash), and emigration due to habitat

loss. Decline of fish abundance could

also be a result of loss of habitat and

disorientation, making the fish more

vulnerable to predators and fishing

pressure. This vulnerability to fishing

pressure was anecdotally suggested by

fishers’ reports of big catches immediately

after the eruption, which later abruptly

declined.

The authors concluded that fish

abundance will take a long time to recover

due to the heavy mortality of corals and

the intermittent lahar flows reaching

coastal areas through the rivers. High

sedimentation on reefs will also change

the community structure of the coral

reef fishes, as these are dependent on

the corals and their associated organisms.

Growth rates, susceptibility to predation

and even recruitment Ofjuveniles might

also be affected. The overall consequence

of this is direct economic losses to the

communities dependent on fishing.

JANUARY 1992

More intriguing information

1. Activation of s28-dependent transcription in Escherichia coli by the cyclic AMP receptor protein requires an unusual promoter organization2. Output Effects of Agri-environmental Programs of the EU

3. Bridging Micro- and Macro-Analyses of the EU Sugar Program: Methods and Insights

4. The name is absent

5. The name is absent

6. The name is absent

7. Synchronisation and Differentiation: Two Stages of Coordinative Structure

8. Campanile Orchestra

9. The name is absent

10. The name is absent