Despite high expectations for operational efficiencies from the use of government-procured commodity foods

in the NSLP, as early as 1965 there is evidence from U.S. congressional hearings that some schools were

having difficulty with the provision of foods, rather than cash, as a portion of federal program funding. The

American School Food Service Association wrote to the Agriculture Committee in 1965 to “request that

commodity purchases be limited” (United States Congress, 1966). The association’s representative

explained that “many costs are involved in storage and transportation at the state and school district levels

which add substantially to the costs of [commodity] purchases.” The letter concluded, “We are confident

that...school districts would effectively utilize reimbursement payments at local markets.”

Recent research from Minnesota provides empirical evidence that this statement remains relevant. Based on

order data from all Minnesota schools in SY 2008-9, it was estimated that for every $1 spent on USDA

commodity products, schools pay on average an additional.12 cents to 27 cents to transport and store those

products, compared to an additional 2 cents to 3 cents cents for commercial equivalents (Peterson, 2009).

This research was restricted to regular packaged commodities and did not include commodities diverted for

further processing. However, the products in the Minnesota analysis constituted over 60% of the collective

commodity order value among schools in the state.

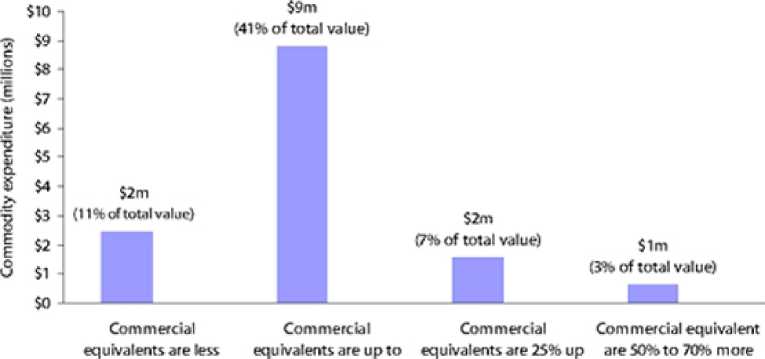

The Minnesota research also compared commodity food prices for 48 products to prices for commercial

equivalents to test the USDA’s claim that the commodity program offers lower unit prices to schools (USDA

Food and Nutrition Service, 2008). As demonstrated in Figure 2, 25% of the USDA commodities were more

expensive than commercial equivalents that were locally available. Once full procurement costs—including

product cost, handling, transportation, administrative labor, warehousing, inventory investment, and cost of

risk to hold inventory—were included in the cost assessment, commercial products on average were

estimated to be 9% less costly for schools than equivalent USDA commodity products.

Figure 2 Commodity Expenditure among Minnesota Schools, School Year 2008-9

expensive (o-12) 2S% more (n-18) toSO% more(rv∏3) (n-5)

Commercial compared to commodity price

Sxm^c∙ M*o∙%αb Dκ-∙**"*r<o*C4wct*of) ДОС*♦> *«o4 0m*X>⅛Aq* Λ⅛y∙m <— Mi O⅜ ∏f ∙Sr⅛ «n *∙φλm p∙cλ∙φ∙β cobmo⅜>a⅝ -4 o∙*wχ**a*H

«ncft CxyMibd βJ4 of toad WMf⅝∣aι-ι MH∣aa∙f∙ ta SY ХЮ*-*

An analysis of Minnesota schools’ commodity spending highlights further concerns about the assumed

financial benefits that the commodity program provides to schools. As also demonstrated in Figure 2,

Minnesota schools directed just 3% of their collective entitlement funding toward commodity products with

the greatest price advantage over commercial products, and 11% of their entitlement value toward

commodity products for which commercial equivalents were less expensive.

The Minnesota research did not offer an opportunity to closely examine the factors that motivate an individual

school district’s ordering decisions. However, it was reported that prices paid for commodities were

substantially different from prices schools had seen at the ordering stage. From SY 2005-6 to SY 2008-9, the

More intriguing information

1. The name is absent2. Globalization, Redistribution, and the Composition of Public Education Expenditures

3. Licensing Schemes in Endogenous Entry

4. Industrial districts, innovation and I-district effect: territory or industrial specialization?

5. Konjunkturprognostiker unter Panik: Kommentar

6. SOME ISSUES CONCERNING SPECIFICATION AND INTERPRETATION OF OUTDOOR RECREATION DEMAND MODELS

7. The name is absent

8. Developing vocational practice in the jewelry sector through the incubation of a new ‘project-object’

9. The name is absent

10. Why unwinding preferences is not the same as liberalisation: the case of sugar