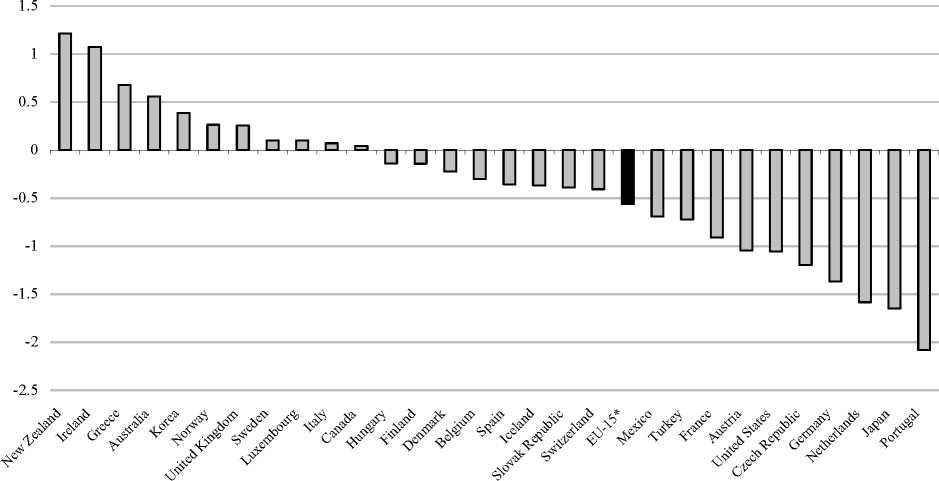

Figure 3. Average output gaps 2001-2006

Per cent of trend GDP

* GDP weighted average.

Source : Data and projections from OECD Economic Outlook 76.

It could of course be argued that current structural policy settings reflect a collective

policy choice and that the associated weaknesses in terms of employment, productivity and

resilience are just the price to be paid for this choice. This argument is often presented with

reference to a particular European “social model”. In practice, however, there is no such thing as a

single European model. Indeed, some smaller European countries combine structural policy

settings that result in much better than average macroeconomic outcomes with social outcomes

that are as good as or better than in the larger euro-area economies.67 Hence, the argument that

weak macroeconomic performance is the price to pay for better social outcomes does not ring

true.

That said, structural reforms cannot generally be assumed to be Pareto improving. If they

were, they would presumably be politically easy to undertake. Rather, structural reforms usually

involve a reduction in rents and those who see their rent reduced can hardly be expected to be in

favour. The case for structural reform thus rests on a weighing of the losses for those who see

their rents reduced against the gains for others. It is a well-known feature of the political economy

of structural reform that those who see their rent reduced tend to be easy to identify, to be exposed

172

More intriguing information

1. Evaluating the Success of the School Commodity Food Program2. The technological mediation of mathematics and its learning

3. ADJUSTMENT TO GLOBALISATION: A STUDY OF THE FOOTWEAR INDUSTRY IN EUROPE

4. Mean Variance Optimization of Non-Linear Systems and Worst-case Analysis

5. The Value of Cultural Heritage Sites in Armenia: Evidence From a Travel Cost Method Study

6. The name is absent

7. Correlation Analysis of Financial Contagion: What One Should Know Before Running a Test

8. Conflict and Uncertainty: A Dynamic Approach

9. References

10. Accurate and robust image superresolution by neural processing of local image representations