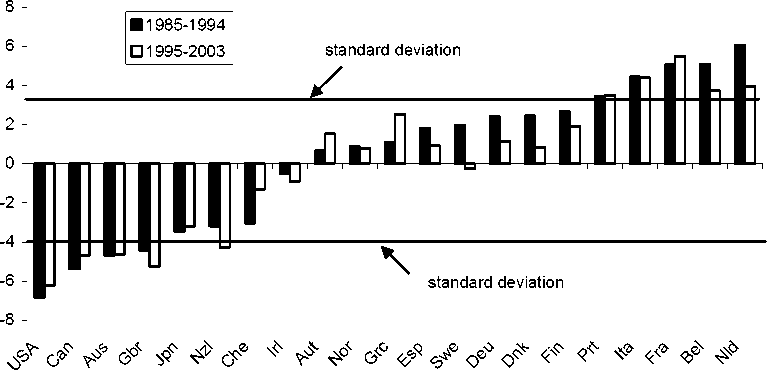

Figure 5. Aggregate structural policy stance indicator

29. As in Duval (2005) we consider 21 countries for which we have annual observations for the

period 1985-2003. Using this dataset, we estimated the following partial-adjustment relationship:

(1) PRIit=λPRIit-1+αSTRit+βΔSTRit+∑γkCONikt-1+δi+εit

k

30. In this relationship PRIit is the level of cyclically-adjusted primary expenditure as a per cent of

GDP in country i in year t. STRit is the overall structural policy stance. It is included to capture the long-run

effect of the structural policy stance on public expenditure. The term ΔSTRit is the change in the structural

policy stance indicator which serves to capture any upfront budgetary cost of structural reform - its

expected sign is negative as predicted by theoretical models such as that reported in Beetsma and Debrun

(2005). CONit-1 is a vector of control variables, δi are country fixed effects and εit is the normally distributed

residual. The method used is ordinary least squares.

31. Following Martinez-Mongay (2002), four control variables have been considered:

• Per capita gross national income at 2000 purchasing power parities. This captures

“Wagner’s law”, which predicts that high-income countries will exhibit higher shares of

public spending in GDP than low-income countries owing to a change in preferences in

favour of public goods and services such as health care, education and social services.

The expected sign is positive.

• The dependency ratio. Ageing puts pressure on notably health care and pension

expenditure, hence a priori one expects public outlays to be higher in countries that

portray a high dependency ratio (measured by the share of people older than 65 in the

total population). The expected sign is again positive.

• Trade openness (sum of exports and imports of goods and services as a per cent of GDP).

A standard finding in the literature is that more open economies will have bigger

governments in order to protect their citizens against cyclical volatility in economic

activity. However, it could also be argued that in a globalising world small open

economies, due to their greater exposure to international competition, will be under

pressure to keep public expenditure low so as to secure competitive gains from a low tax

burden. Accordingly, the net effect on government size is ambiguous.

54

More intriguing information

1. What Drives the Productive Efficiency of a Firm?: The Importance of Industry, Location, R&D, and Size2. The name is absent

3. Bird’s Eye View to Indonesian Mass Conflict Revisiting the Fact of Self-Organized Criticality

4. The name is absent

5. IMPROVING THE UNIVERSITY'S PERFORMANCE IN PUBLIC POLICY EDUCATION

6. Large Scale Studies in den deutschen Sozialwissenschaften:Stand und Perspektiven. Bericht über einen Workshop der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft

7. Cyber-pharmacies and emerging concerns on marketing drugs Online

8. Higher education funding reforms in England: the distributional effects and the shifting balance of costs

9. Micro-strategies of Contextualization Cross-national Transfer of Socially Responsible Investment

10. Perfect Regular Equilibrium