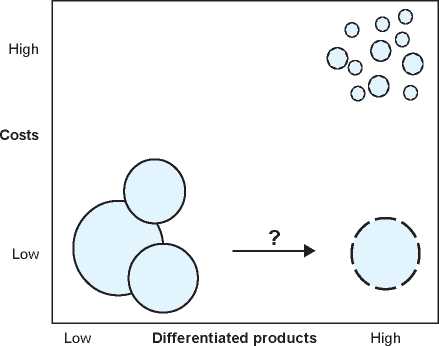

2. Strategic map of commercial banking

Note: “Differentiated products” refers to the degree of personal

service, customized products, and/or brand image offered

by a bank.

to pay relatively high prices. Hypo-

thetical large regional or nationwide

banks are located in the lower left

corner. These banks operate at large

scale, incur low unit costs, operate

through a combination of physical

branches and the Internet, and offer

commodity-like products for which

customers are less willing to pay high

prices. In this example, the most prof-

itable strategy is to locate in the lower

right hand corner, operating at large

scale (which reduces unit costs) and

offering differentiated products (which

command high prices).

By definition, small banks cannot

migrate to this most profitable strate-

gy—unless they become large banks.

However, it might be possible for

large banks to implement this strate-

gy, depending on the skill with which

they can deploy personalized products

over electronic delivery channels.

Large banks currently customize finan-

cial services for some of their large

business clients (for example, M&A

financing); if large banks can custom-

ize financial services for retail and

small business customers on a large

scale basis—perhaps using electronic

delivery channels to reduce production

costs and make these services more

convenient—they will be able to take

away some of small banks’ most prof-

itable customers. The low-cost struc-

tures, wide product offerings, and

differentiated brand

images of large banks

would be difficult for

small banks to over-

come. However, if large

banks can only mass

produce commodity-

like products (such as

credit-scored small

business loans, stan-

dardized insurance

products, or automat-

ed asset management

without personalized

investment advice),

then relationship bank-

ing will continue to

provide a profitable

niche for small banks.

Conclusion

Just as the wave of do-

mestic bank mergers has produced

the first nationwide banks, the im-

plementation of new electronic deliv-

ery channels threatens to transform

the banking landscape once again.

This Fed Letter explores the prospects

for small commercial banks in a

post-merger-wave, post-Internet

banking industry. I argue that the fu-

ture success of small banks hinges on

their traditional advantages in rela-

tionship banking and personalized

financial services and on how these

advantages stack up against the com-

bination of low costs, convenient

one-stop shopping, and powerful

brand images that large banks may

be able to wield over electronic de-

livery channels.

As we consider how the Internet will

transform banking, it is important to

remember that this new delivery

channel is unlikely to change the

fundamental nature of the financial

products delivered over it. Consider

an example from e-commerce.

Amazon.com and its competitors

may be making the traditional book-

store obsolete, but they have not (yet)

made the printed book obsolete—

ironically, these Internet firms deliver

the books they sell not electronically,

but by surface mail. Whether e-bank-

ing leads to a substantial change in

the number and/or size of commer-

cial banks or just changes the way

that existing banks deliver financial

services to their customers remains for

now an open question.

—Robert DeYoung

Senior economist and economic advisor

1Robert DeYoung, 1999, “Mergers and the changing

landscape of commercial banking (Part I),” Chicago

Fed Letter, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, No. 145,

September.

2For a discussion of the post-merger experiences of

Bank One, First Union, and other ultra-acquisitive

banking companies, see Euromoney, 1999, “When

cutting cost is not enough,” November, pp. 58-60.

3By mid-1999, the top ten credit card issuers in the

U.S. held more than a 75% market share (see Chica-

go Tribune, 1999, “Cards getting less credit for bank

industry growth,” August 27). For evidence on scale

economies and growing concentration mortgage

banking, see Clifford V. Rossi, 1998, “Mortgage

banking cost structure: Resolving an enigma,”

Journal of Economics and Business, Vol. 50, No. 2.

pp. 219-234, and Mitchell Stengel, 1995, “From

traditional mortgage lending to modern mortgage

banking,” Office of the Comptroller of the Currency,

Quarterly Journal, No. 4, pp. 11-18.

4See Chicago Tribune, 1999, “Allstate points to new

future,” November 11.

5See Loretta J. Mester, 1999, “Banking industry con-

solidation: What’s a small business to do?” Federal

Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, Business Review, Janu-

ary/February, pp. 3-16.

6For an introduction to strategic maps, see Michael

E. Porter, 1980, Competitive Strategy, New York: Free

Press.

Michael H. Moskow, President; William C. Hunter,

Senior Vice President and Director of Research; Douglas

Evanoff, Vice President, financial studies; Charles

Evans, Vice President, macroeconomic policy research;

Daniel Sullivan, Vice President, microeconomic policy

research; William Testa, Vice President, regional

programs and economics editor; Helen O’D. Koshy,

Editor.

Chicago Fed Letter is published monthly by the

Research Department of the Federal Reserve Bank

of Chicago. The views expressed are the authors’

and are not necessarily those of the Federal

Reserve Bank of Chicago or the Federal Reserve

System. Articles may be reprinted if the source is

credited and the Research Department is

provided with copies of the reprints.

Chicago Fed Letter is available without charge from

the Public Information Center, Federal Reserve

Bank of Chicago, P.O. Box 834, Chicago, Illinois

60690-0834, tel. 312-322-5111 or fax 312-322-5515.

Chicago Fed Letter and other Bank publications are

available on the World Wide Web at http://

www.frbchi.org.

ISSN 0895-0164

More intriguing information

1. Notes on an Endogenous Growth Model with two Capital Stocks II: The Stochastic Case2. Should informal sector be subsidised?

3. Linking Indigenous Social Capital to a Global Economy

4. Brauchen wir ein Konjunkturprogramm?: Kommentar

5. The name is absent

6. The name is absent

7. FOREIGN AGRICULTURAL SERVICE PROGRAMS AND FOREIGN RELATIONS

8. POWER LAW SIGNATURE IN INDONESIAN LEGISLATIVE ELECTION 1999-2004

9. The name is absent

10. The name is absent