in financially distressed farm states. All

of the Corn Belt states reported in-

creased personal bankruptcy levels

during this period, with filings up 45%

in Iowa and 22% in Missouri. In the

Plains states, North Dakota and Texas

reported increases above 30%, and

South Dakota, Kansas, and Oklahoma

showed gains above 20%. On the

other hand, more than half of the

northeastern states, for example, re-

ported increases of only about 10%.

Although not all of the increase in

personal bankruptcy filings in 1985

can be explained by the agricultural

slump, the disparity in bankruptcy

increases between farm and nonfarm

states indicates that personal bankrupt-

cy levels were dramatically affected by

a regional shock to the economy.

In 1986, a sudden plunge in the world

price of oil led to a recession in the Oil

Patch states, mainly in the Southwest

(Texas, Oklahoma, Louisiana, and

Arkansas), and the West (Alaska, Cali-

fornia, Wyoming, Arizona, and Colo-

rado) . Domestically, the spot price of

West Texas intermediate crude oil fell

from an average of $30 per barrel in

November 1985, to an average of $11

per barrel in July 1986. The plunge in

the price of oil had severe financial

consequences in the oil and gas indus-

tries, and in several petroleum-related

sectors. The number of new crude

petroleum and natural gas wells

drilled was almost halved between

1985 and 1986, while oil and gas ex-

traction output fell 13% during the

same period. Unemployment in the

mining sector and petroleum-related

industries rose sharply, as did unem-

ployment rates in the states with the

largest production of crude petroleum

and natural gas. In the affected states,

unemployment averaged over 8% in

the West and almost 10% in the South.

These unemployment rates were con-

siderably higher than the national rate

of 7% and the average rate of 5% in

the Northeast. Again, the states with

the highest unemployment rates also

recorded the largest increases in per-

sonal bankruptcies.

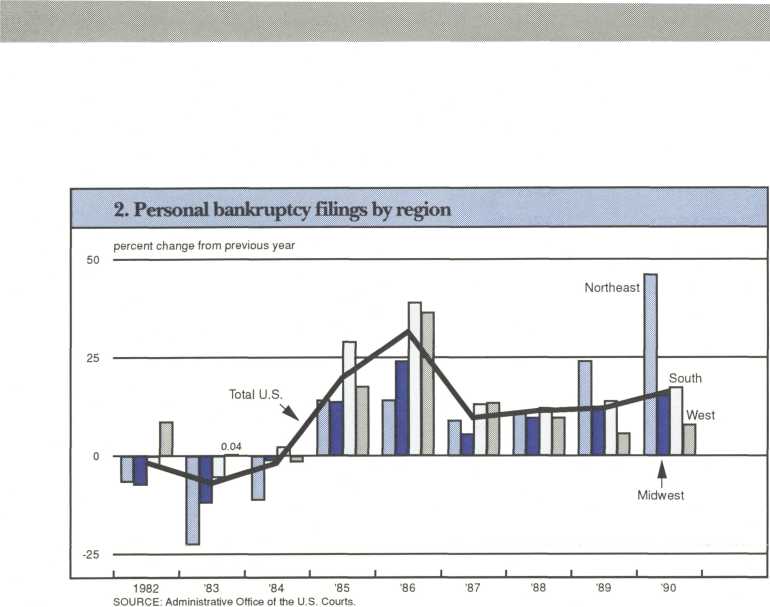

In 1986, personal bankruptcy filings

jumped 32% nationally, with a 39%

increase in the South and a 36% rise

in the West (see Figure 2). Moreover,

personal bankruptcies rose by more

than 50% in Alaska, Arizona, Colo-

rado, Texas, and Oklahoma, and by

more than 30% in California, Wyo-

ming, and Louisiana. Both the North-

east and the Midwest, on the other

hand, reported more moderate up-

swings in the number of filings in

1986, with increases of 14% and 24%,

respectively.

Such considerable disparity in the

magnitude of bankruptcy increases

among regions was mostly due to the

fact that the negative economic shock,

which contributed to the increase in

personal bankruptcies, was localized in

the Oil Patch states. One study indicat-

ed, however, that personal bankruptcies

continued to grow at the national level

even when five of the major oil-produc-

ing states were excluded from the calcu-

lations.2 One possible explanation for

this phenomenon is that although the

initial economic shock was confined to

the Oil Patch states, its financial conse-

quences were more widespread, as oth-

er petroleum-related sectors were affect-

ed by the oil slump. Moreover, the

unprecedented increase in consumer

debt during the 1980s made it more

difficult for those households affected

by the oil recession to deal with unex-

pected financial strain.

Because personal bankruptcy filings

sometimes respond to recessions with a

lag, economic downturns can affect

bankruptcy levels over extended periods

of time. When individuals are laid off,

they do not file for bankruptcy immedi-

ately. They first try to find new jobs,

migrate to economically healthier re-

gions, or borrow money from their

families and friends. Studies show that

approximately 80% of all bankrupt

individuals are employed when they file

for bankruptcy. However, their job

tenure is usually shorter than that of the

average population, and their salary

lower compared to other workers in the

same position. This suggests that unem-

ployment originally forced them to look

for another occupation—often a lower

paying job—before filing for bankrupt-

cy. Moreover, the fact that personal

bankruptcies sometimes respond to

economic downturns with a lag ex-

plains, in part, why personal bankrupt-

cies did not decline after 1986, although

the rate of increase slowed considerably

during the three years that followed.

1989-1990: the real estate slump

During the latter part of the 1980s,

changes in the number of personal

bankruptcy filings again varied consider-

ably among states. During the 1987-

1990 period, personal bankruptcies rose

at an average annual rate of 13% at the

national level (see Figure 2). Although

filings also rose at the regional level,

certain states reported smaller increases,

while other states reported declines.

The disparity can be explained by an-

other localized economic disturbance;

More intriguing information

1. Wirtschaftslage und Reformprozesse in Estland, Lettland, und Litauen: Bericht 20012. The name is absent

3. Regional dynamics in mountain areas and the need for integrated policies

4. The name is absent

5. The name is absent

6. Tobacco and Alcohol: Complements or Substitutes? - A Statistical Guinea Pig Approach

7. Plasmid-Encoded Multidrug Resistance of Salmonella typhi and some Enteric Bacteria in and around Kolkata, India: A Preliminary Study

8. Ronald Patterson, Violinist; Brooks Smith, Pianist

9. Intertemporal Risk Management Decisions of Farmers under Preference, Market, and Policy Dynamics

10. A Pure Test for the Elasticity of Yield Spreads