More precisely, the increase in d increases the intensity of multi-tasking and

the output level immediately after the shock, and this effect persists also in the

long run. The fraction of the workforce in the human resources service, the level

of human capital and the allocation of time in favour of production, on the other

hand, increase immediately after the shock on d, but then return to their initial

levels since this shock does not affect their long run values. Intuitively, an increase

in d corresponds to a reduction in coordination costs and represents therefore the

same kind of qualitative productivity shock as a rise in the technological parameter

A.

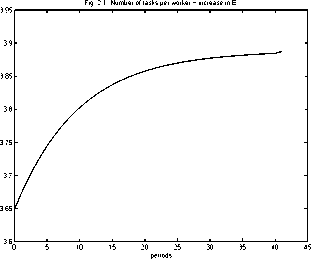

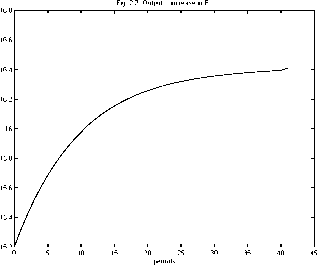

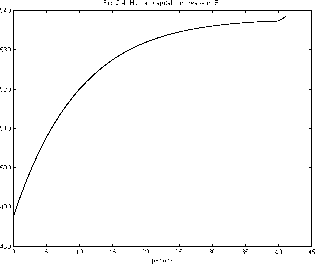

The last situation analyzed is an increase in the efficiency of human capital E .

In this case, we have shown analytically that a rise in E has a long run effect on

the number of tasks performed per worker, on the level of output and on the level

of human capital (that all increase).

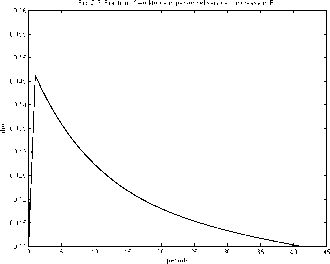

In the short run (Figures 2.1 - 2.4), the timing of the effects of the shock on

the different variables is different from the previous cases. In effect, the number of

tasks per worker n gradually increases after the rise in E and reaches, in the long

run, a level higher than the initial one (while in the other cases examined there is

immediately the jump in the variable, that then remains at the new value). Following

the rise in E , output also increases gradually reaching the new long run level, and

the same happens for the level of human capital. On the contrary, the fraction of

the workforce in the human resources service and the allocation of time in favour

of productive activity initially increase but then return to their initial levels, since

their long run values are not affected by the shock on E .

22

More intriguing information

1. Competition In or For the Field: Which is Better2. The name is absent

3. The name is absent

4. The Context of Sense and Sensibility

5. The name is absent

6. Proceedings of the Fourth International Workshop on Epigenetic Robotics

7. 101 Proposals to reform the Stability and Growth Pact. Why so many? A Survey

8. The name is absent

9. CREDIT SCORING, LOAN PRICING, AND FARM BUSINESS PERFORMANCE

10. Migration and Technological Change in Rural Households: Complements or Substitutes?