14

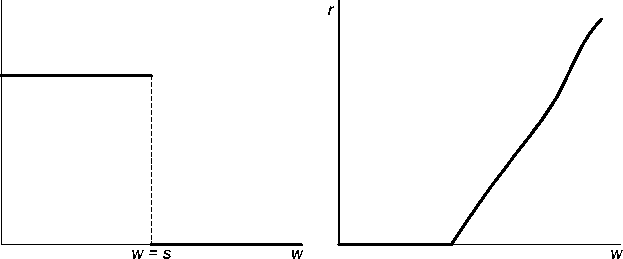

Figure 5. Activism and Contribution Decisions

4.3.2. Within-Group Inequality in Wealth. Let us now examine the effect of increased within-

group inequality in wealth. The simplest change in within-group inequality that does not per-

turb the correlation between resources and religious extremism is one that generates a Lorenz-

change in wealth for every level of radicalism x, while leaving the population distribution of

x completely unaffected. In what follows, we consider the implications of a deterioration in

wealth distribution that has exactly this form.

To study the effects of this change, it will be useful to recall both the activism and resource

contribution decisions made by various individuals. Figure 5 summarizes these. In our model,

the activism decision is essentially mercenary (up to an inability to switch religious sides), and

so is very simple. Each individual below the equilibrium compensation threshold supplies “one

unit” of activism, and everyone above supplies none (panel A of Figure 5). The resource contri-

butions r will depend on both radicalism x and wealth w ; panel B draws r as a function of w

for some given level of x. For individuals with low wealth, r is set at zero; for them, (3) holds

with an inequality. Thereafter r becomes positive and continues to rise as wealth increases.

Depending on how the distributional change affects earning capacities to the left and right

of the activism threshold, there are — in principle — a number of cases to study. We illustrate

by considering what we consider to be the most reasonable situation: that the worsening of in-

equality permits no one below the activism threshold to gain in wealth. Typically, this threshold

would be quite low, and only the poor would participate. It is formally possible, but very un-

likely, that a Lorenz-worsening of the overall distribution would actually permit such individuals

to gain in wealth.

PROPOSITION 5. Fora given group, suppose that for each level of radicalism, wealth inequality worsens

in the sense of Lorenz-deterioration, and that no activist in the going equilibrium gains wealth. Then,

evaluated at the going equilibrium, the equilibrium response of the group must rise, so that in the new

equilibrium there will be greater activism for the group.

Thus, while inequality across groups may have ambiguous effects on conflictual tendencies,

the verdict on inequality within groups is more clearcut. Inequality tends to heighten conflict

for two reasons. First, heightened inequality will generally increase the supply of individuals

with low opportunity costs of activism, and in this way the supply of activists. Second and

more importantly, it shifts wealth from those who contribute little or no resources to conflict

and concentrates that money in the hands of those who are in a better position to make such

contributions. The formal counterpart of this intuitive argument comes from taking another look

More intriguing information

1. Gender stereotyping and wage discrimination among Italian graduates2. A Study of Adult 'Non-Singers' In Newfoundland

3. Competition In or For the Field: Which is Better

4. The name is absent

5. Tobacco and Alcohol: Complements or Substitutes? - A Statistical Guinea Pig Approach

6. Langfristige Wachstumsaussichten der ukrainischen Wirtschaft : Potenziale und Barrieren

7. BODY LANGUAGE IS OF PARTICULAR IMPORTANCE IN LARGE GROUPS

8. Second Order Filter Distribution Approximations for Financial Time Series with Extreme Outlier

9. Are Public Investment Efficient in Creating Capital Stocks in Developing Countries?

10. FUTURE TRADE RESEARCH AREAS THAT MATTER TO DEVELOPING COUNTRY POLICYMAKERS