variables), a reasonable facsimile of a price-quantity

demand curve if differences in on-site costs reflect

differences solely in unit prices of ancillary inputs,

but not if they reflect differences in demands for

ancillary inputs at given prices. In the latter case, the

number of days taken could plausibly increase with

an increase in daily on-site expenses, despite the

apparent predominance of empirical evidence to the

contrary.

A diagrammatic interpretation of the distinction

is as follows:

On-Site

Costs

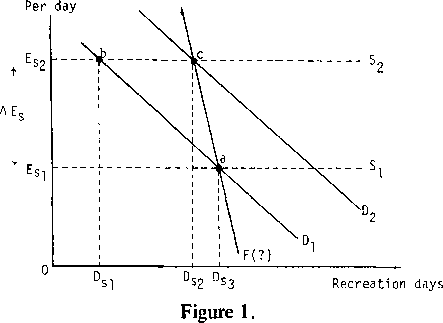

In Figure 1 the curves labeled Dj and D2 depict

hypothetical demand curves. They are demand curves

by virtue of their showing the relationship, other

things being equal, between daily on-site costs and

total usage (quantity demanded) of a given facility.

An initial equilibrium, point a, is defined, with

Ds3 visitor days being consumed at daily on-site costs

of Es . Next an increase in daily ancillary on-site

costs, from ESj to Es^, is posited. The type of cost

increase valid for treatment as a price proxy is

completely independent of any shift in on-site-cost

demand for the given site. For that type of price

change the predicted decline in quantity demanded

would be from Dc to Dc as read from demand

curve Di. If, however, some part of the same change

in on-site costs were due to an improvement in site

quality, for example, the quality improvement would

also induce an upward shift of demand from Dj to,

say, D2. Thus, instead of a movement to point b on

Di, the equilibrium would move to a point such as c

on D2 and on the curve labeled F(7).F(?) in this

example would clearly underestimate the on-site-cost

elasticity of demand.

By the same reasoning it can be shown that if a

change in site quality induces a decline in daily

on-site expenditures, the resulting F(?) would

overestimate the true on-site elasticity of demand.

The question, of course, is: Are ancillary on-site costs

more or less in site-proxy than a site-quality demand

shifter? The answer to that question is crucial to

explaining or predicting recreationists’ reactions to

changes in daily on-site costs.

There are no doubt many types of study areas in

which it would suffice merely to mention the absence

of compelling reasons for suspecting that on-site costs

reflect demand shifts instead of price differences. At

the same time, some empirical evidence on the

presence or absence of a relationship between on-site

costs and other possible demand shifters would

enhance the usefulness of on-site costs in their role as

a price proxy.

Travel Costs

Travel costs constitute a tempting price proxy,

both because of their prominence in the typical

recreationist’s budget and because data on them are

so easily obtainable. It is not altogether certain,

however, that travel costs are, in all cases, a better

index of site price than of quantities purchased of

ancillary travel inputs.

Moreover, only if the sole purpose of a trip is to

recreate on a given site can costs of travel be

considered a valid proxy price for recreational

opportunities of that site. The appropriateness of the

proxy price varies inversely with the strength of other

reasons for the trip. It is not necessary to require the

visitor to know precisely where he is going the

moment he leaves his home. It is enough that he gets

no utility from his trip apart from the on-site

pleasures of that particular site. To assume so much

should be done carefully.

There are suggestions as to how total travel costs

might be adjusted to remove the influence of other

benefits. One is to exclude from consideration the

recreationist whose visit to the site is not the sole

reward for his travels. A more typical approximation

is to exclude from the sample of recreationists those

whose visit is not the major reason for the trip. That

might be rational, as approximations go, for visitors

to a facility with such unique and Unduplicatable

facilities as those of a Grand Canyon or a

Yellowstone, where for reasons of remoteness, as well

as uniqueness, the typical visitor may well be

enjoying the high point of his trip.5

Applying the same rule of sample selection to

any campsite may, however, exclude the typical

5The subject matter of Clawson and many others does belong to this resource-based type of facility.

167

More intriguing information

1. The name is absent2. DISCRIMINATORY APPROACH TO AUDITORY STIMULI IN GUINEA FOWL (NUMIDA MELEAGRIS) AFTER HYPERSTRIATAL∕HIPPOCAMP- AL BRAIN DAMAGE

3. Gender and aquaculture: sharing the benefits equitably

4. AN EXPLORATION OF THE NEED FOR AND COST OF SELECTED TRADE FACILITATION MEASURES IN ASIA AND THE PACIFIC IN THE CONTEXT OF THE WTO NEGOTIATIONS

5. The name is absent

6. Computing optimal sampling designs for two-stage studies

7. Social Balance Theory

8. The name is absent

9. Globalization, Divergence and Stagnation

10. The name is absent