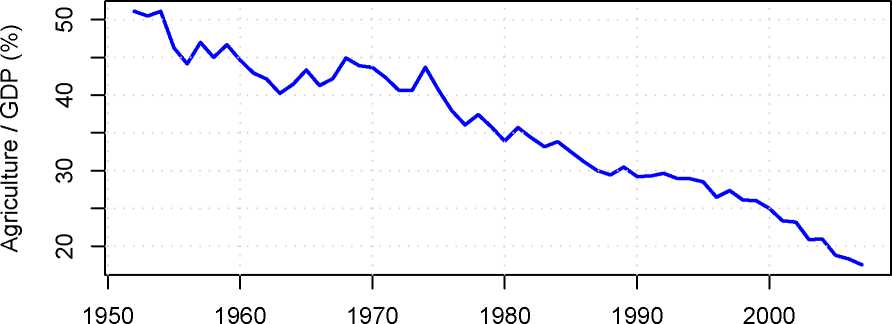

Figure 1 Agriculture/GDP ratio

2.3.1 Monsoon shocks matter less

In the India of old, there was no conventional business cycle (Patnaik and Sharma, 2002).

A good year was one with a good monsoon and a downturn was generally about a bad

monsoon. These developments played out over a short horizon of one or two years. Output

fluctuations significantly reflected a succession of uncorrelated monsoon shocks - it was not

a conventional business cycle.

A major change in the behaviour of the Indian macroeconomy, then, consists of the

rapidly dropping importance of agriculture. As Figure 1 shows, the share of agriculture in

GDP has dropped quite sharply from 27% in 1996-97 to 17.5% in 2006-07.

In addition, the vulnerability of agriculture to the monsoon is declining through the

spread of irrigation. The linkages between agriculture and the economy are weaken-

ing. Putting these factors together, the domination of monsoon shocks in influencing

the macroeconomy has been substantially attenuated.

Linearly extrapolating into the future, agriculture may drop below 10% of GDP by

2013, by which time it would be an essentially insignificant part of Indian macroeconomics.

Agriculture will stop mattering for macroeconomics; within a few years, it will be just

another industry.

2.3.2 A more conventional business cycle

In recent years, large fluctuations of inventory and investment of firms have taken place, in

line with the mainstream notions of a conventional business cycle that is found in mature

market economies.

Several factors are at work here. In the old world, firms did not have operational flex-

ibility to invest. Firms were static, with fixed technology and minute product variation

More intriguing information

1. A Classical Probabilistic Computer Model of Consciousness2. THE EFFECT OF MARKETING COOPERATIVES ON COST-REDUCING PROCESS INNOVATION ACTIVITY

3. INTERPERSONAL RELATIONS AND GROUP PROCESSES

4. The name is absent

5. The name is absent

6. Pursuit of Competitive Advantages for Entrepreneurship: Development of Enterprise as a Learning Organization. International and Russian Experience

7. Benchmarking Regional Innovation: A Comparison of Bavaria, Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland

8. News Not Noise: Socially Aware Information Filtering

9. Natural Resources: Curse or Blessing?

10. POWER LAW SIGNATURE IN INDONESIAN LEGISLATIVE ELECTION 1999-2004