BMC Medical Research Methodology 2008, 8:45

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2288/8/45

ing in research synthesis.) This process created a total of

36 initial codes. For example, some of the text we coded

as "bad food = nice, good food = awful" from one study

[56] were:

'All the things that are bad for you are nice and all the

things that are good for you are awful.' (Boys, year 6)

[[56], p74]

'All adverts for healthy stuff go on about healthy things. The

adverts for unhealthy things tell you how nice they taste.'

[[56], p75]

Some children reported throwing away foods they knew had

been put in because they were 'good for you' and only ate

the crisps and chocolate. [[56], p75]

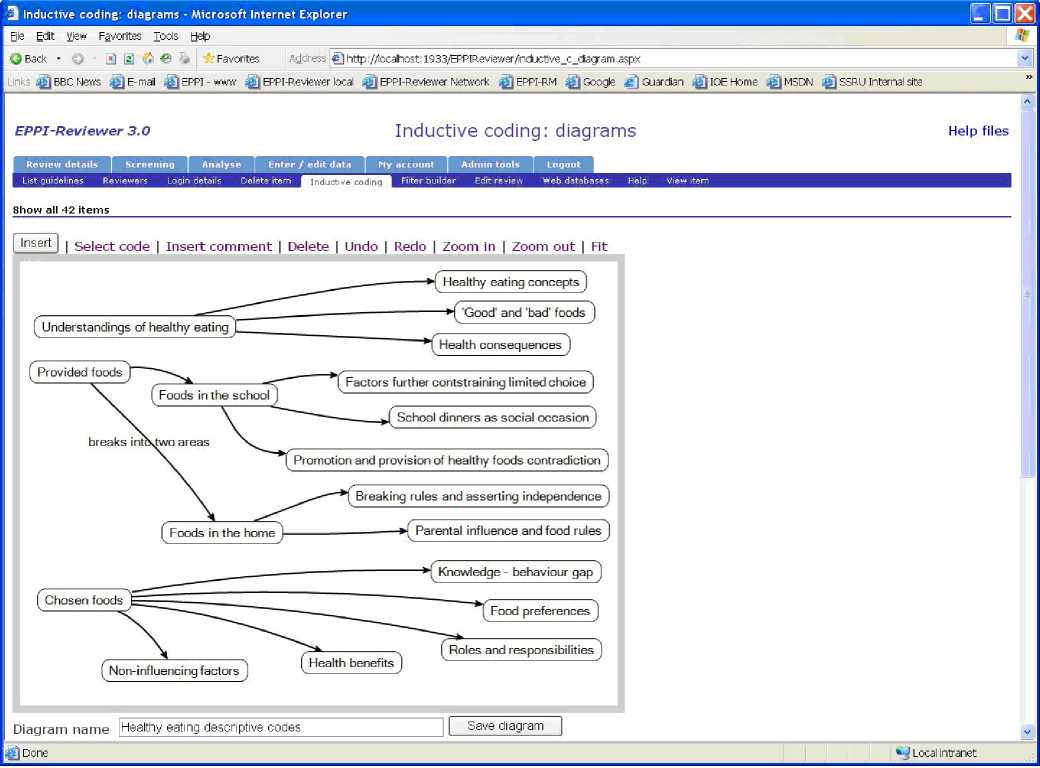

Reviewers looked for similarities and differences between

the codes in order to start grouping them into a hierarchi-

cal tree structure. New codes were created to capture the

meaning of groups of initial codes. This process resulted

in a tree structure with several layers to organize a total of

12 descriptive themes (Figure 2). For example, the first

layer divided the 12 themes into whether they were con-

cerned with children's understandings of healthy eating or

influences on children's food choice. The above example,

about children's preferences for food, was placed in both

areas, since the findings related both to children's reac-

tions to the foods they were given, and to how they

behaved when given the choice over what foods they

might eat. A draft summary of the findings across the stud-

ies organized by the 12 descriptive themes was then writ-

ten by one of the review authors. Two other review

authors commented on this draft and a final version was

agreed.

Figuire 2ips between descriptive themes

relationships between descriptive themes.

Page 6 of 10

(page number not for citation purposes)

More intriguing information

1. Ruptures in the probability scale. Calculation of ruptures’ values2. Perfect Regular Equilibrium

3. The name is absent

4. Bargaining Power and Equilibrium Consumption

5. Labour Market Institutions and the Personal Distribution of Income in the OECD

6. Commitment devices, opportunity windows, and institution building in Central Asia

7. The demand for urban transport: An application of discrete choice model for Cadiz

8. Pricing American-style Derivatives under the Heston Model Dynamics: A Fast Fourier Transformation in the Geske–Johnson Scheme

9. The name is absent

10. EFFICIENCY LOSS AND TRADABLE PERMITS