reach educational goals. Furthermore, others say if you know proc-

ess, you don’t need to be an expert in the subject being discussed.

I would like to suggest that extension educators need to balance

their use of process skills and educational expertise in order to have

optimum outcomes in public policy education. While sitting in a

Family Community Leadership meeting with volunteers and staff

members, a question was asked, “Now, what process is occurring

here?” Wayne Shull, the staff member who was the presenter, did a

quick analysis of what process was taking place. My thought was,

“My, he’s smooth, we weren’t aware of the process techniques

being used.” When process is obvious it may become annoying and

distract from the issue being discussed.

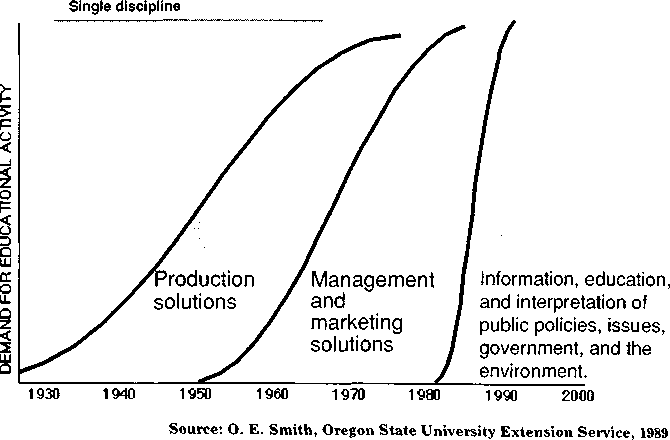

Demands for extension education are changing. 0. E. Smith, di-

rector of the Oklahoma State University Extension Service, uses this

diagram (Figure 1) to illustrate current expectations of extension ed-

ucation. Early in the century, expectations for agricultural extension

programs centered on production solutions and usually involved a

single discipline in the solution. During the boom years of the 1950s

problems became more complex and required expertise that crossed

disciplines. In agriculture, this was accomplished by marketing and

management education as well as education about production. Basic

production, marketing and management education are needed for

Figure 1. The Changing Demand for Extension Education

Interagency cooperation

Interdisciplinary cooperation

122

More intriguing information

1. The name is absent2. TOMOGRAPHIC IMAGE RECONSTRUCTION OF FAN-BEAM PROJECTIONS WITH EQUIDISTANT DETECTORS USING PARTIALLY CONNECTED NEURAL NETWORKS

3. The name is absent

4. The name is absent

5. The name is absent

6. The name is absent

7. Do imputed education histories provide satisfactory results in fertility analysis in the Western German context?

8. The name is absent

9. Pricing American-style Derivatives under the Heston Model Dynamics: A Fast Fourier Transformation in the Geske–Johnson Scheme

10. Political Rents, Promotion Incentives, and Support for a Non-Democratic Regime