A THEORETICAL GROWTH MODEL FOR IRELAND

251

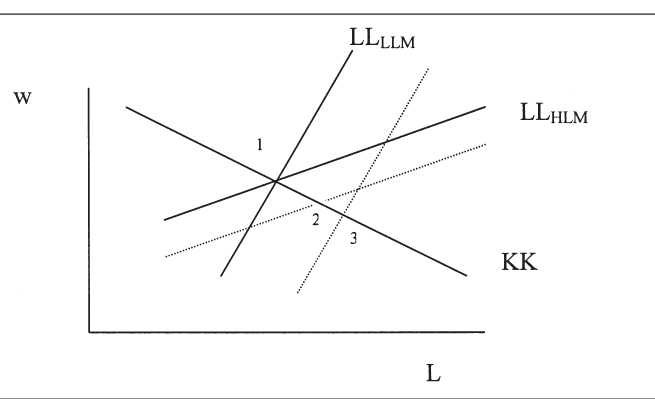

of labour mobility (i.e., the higher is ⅞) and the greater the degree of capital

mobility (i.e., the lower is Φ2), the greater the effect of these shocks on long-

run equilibrium GNP.

Figure 1: Outcome of a Labour-Market Shock, with Low and

High Labour Mobility

III THE FORMAL MODEL

We try to write down a simple, parsimonious model which can capture the

main internal and external channels of importance in the Irish growth of the

1990s. As discussed above, the essential features of the analysis are a

combination of high capital mobility (in the form of FDI) and labour mobility.

We simplify by assuming that all capital accumulation is financed by foreign

borrowing (and hence owned by foreign investors). Domestic residents receive

and consume only their wage income. While this is obviously an extreme

assumption, nothing of consequence in our analysis depends on it, and it has

the benefit of allowing us to highlight the gap between national output and

national income, or GDP and GNP, a distinction that is of great importance for

the Irish economy.

The structure of the model is as follows. Throughout we will assume just

one sector of production, which uses capital and labour. All capital represents

FDI, and must earn a given world rate of return plus a country specific risk

premium. Labour supply comes from domestic households. Households are

assumed to make a choice between supplying labour in the home economy, at

More intriguing information

1. The name is absent2. Barriers and Limitations in the Development of Industrial Innovation in the Region

3. Spectral calibration of exponential Lévy Models [1]

4. Aktive Klienten - Aktive Politik? (Wie) Läßt sich dauerhafte Unabhängigkeit von Sozialhilfe erreichen? Ein Literaturbericht

5. Outline of a new approach to the nature of mind

6. Understanding the (relative) fall and rise of construction wages

7. The name is absent

8. Evolutionary Clustering in Indonesian Ethnic Textile Motifs

9. Can we design a market for competitive health insurance? CHERE Discussion Paper No 53

10. El Mercosur y la integración económica global