provided by Research Papers in Economics

ESSAYS ON ISSUES

THE FEDERAL RESERVE BANK JULY 2000

OF CHICAGO

NUMBER 155

Chicago Fed Letter

Understanding the

(relative) fall and rise

of construction wages

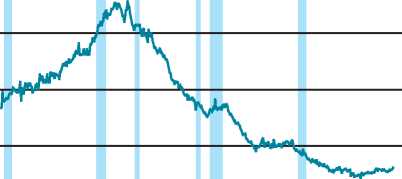

Over the last four years, wages of con-

struction workers have risen modestly

relative to those of other workers, par-

tially reversing what had been a near-

ly continuous 25 year decline. As

figure 1 shows, the ratio of average

hourly earnings in the construction

industry to that of all private produc-

tion workers rose throughout the

1960s. In the early 1970s, when the

construction industry was at the center

of the concerns that led to the impo-

sition of wage and price controls, con-

struction workers earned about 45%

more per hour than the average

worker.1 Following that peak, however,

relative construction wages declined

steadily until 1995 when they were

only 15% above average. The recent

rebound has seen that figure increase

to about 17%.

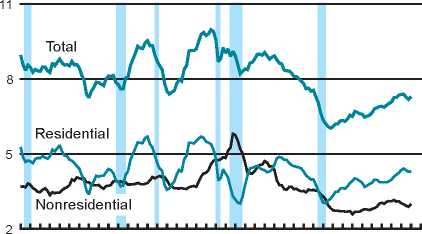

The rebound in construction wages

has come in the midst of a construc-

tion industry boom. Housing demand

is at historically high levels and short-

ages of construction labor have been

reported across the country. The con-

struction sector has gained in its share

of gross domestic product (GDP) and

employment, as shown in figures 2

and 3. Moreover, the gap between

the construction unemployment rate

and the overall unemployment rate

recently narrowed to its lowest level

in the past three decades, indicating

the tightest labor market in construc-

tion since the 1960s (see figure 4).

Indeed, given the tightness of con-

struction industry labor markets, it

might seem surprising that construc-

tion wages have not risen even faster.

Understanding the forces that have

restrained wage growth during the

recent boom as well as producing the

long decline in relative

wages since the early

1970s requires a look

at how the industry has

changed over the last

three decades and how

its role in the U.S. econ-

omy has developed.

Impact of economy-

wide changes

Certain economy-wide

changes seem to have

affected the construc-

tion industry more

than other industries.

Investment in struc-

tures increased in the

1990s, but declined sig-

nificantly as a percent

of GDP from the late

1970s to the early 1990s.

The upward movement

of residential construc-

tion has masked the

often flat level of non-

residential construction

(see figure 2). Although

the 1980s experienced

great economic growth,

investment in structures

lagged behind the rest

of the economy. This

seems to reflect the

cyclical nature of the

construction industry

as overbuilding in the

1970s resulted in less

activity in the following decade.

Regional economic growth in the

last two decades was also uneven, as

the South and West grew faster than

the rest of the U.S. This geographic

tilt to growth may have lowered rela-

tive wages in the construction indus-

try since wages tended to be lower in

the higher growth regions, aside

from the Far West. Average hourly

1. Construction to private hourly earnings

percent

150 ---

110..........................................

1960 ’64 ’68 ’72 ’76 ’80 ’84 ’88 ’92 ’96 ’00

Note: Monthly data. Shaded areas indicate recessions as defined

by the National Bureau of Ecomomic Research.

Source U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics,

Current Population Survey.

2. Structures investment share of GDP

percent

1960 ’64 ’68 ’72 ’76 ’80 ’84 ’88 ’92 ’96 ’00

Note: Quarterly data. Shaded areas indicate recessions as defined

by the National Bureau of Ecomomic Research.

Source: U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis,

National Income and Product Accounts.

earnings in construction (though not

available for all states) currently vary

from highs of $26.87 for Alaska and

$24.76 for New York to a low of $13.74

for North Carolina in April.2

National labor market trends have

also played a part in restraining the

relative wages of construction workers.

For instance, the mix of workers in

the U.S. has changed dramatically

More intriguing information

1. A Theoretical Growth Model for Ireland2. Enterpreneurship and problems of specialists training in Ukraine

3. The name is absent

4. The Modified- Classroom ObservationScheduletoMeasureIntenticnaCommunication( M-COSMIC): EvaluationofReliabilityandValidity

5. The name is absent

6. Testing the Information Matrix Equality with Robust Estimators

7. The name is absent

8. The name is absent

9. Reform of the EU Sugar Regime: Impacts on Sugar Production in Ireland

10. Elicited bid functions in (a)symmetric first-price auctions