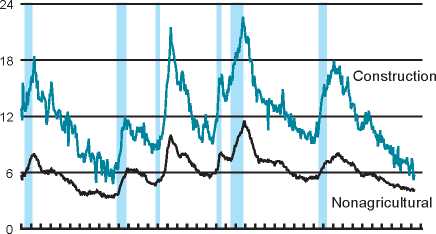

percent

1960 ’64 ’68 ’72 ’76 ’80 ’84 ’88 ’92 ’96 ’00

Notes: W + S is wage and salaried. Monthly data. Shaded areas indicate

recessions as defined by the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Source U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics,

Current Population Survey.

4. Private W + S unemployment rate

also factor into the lessening of union

influence over wages in the construc-

tion industry. “Critics of these laws

generally claim that the creation of

an artificial (union-based) wage floor

reduces competition and tends to

inflate building costs.”13 However, in

1993 Congress increased the thresh-

olds on the size of construction pro-

jects to which the Davis-Bacon Act

of 1931 applies. For new construction

under $100,000 and repair projects

under $25,000 firms now do not have

to pay prevailing wages. This has al-

lowed construction firms to win more

federal contracts without paying union

wages, thus weakening union power.

Another area of change in prevailing

wage laws allows helpers to replace

higher paid apprentices at job sites.

The helpers are less skilled than ap-

prentices and can do more of the

manual labor that otherwise would

have to be done at greater cost. An

additional tactic to lower costs is to

hire apprentices outside of approved

programs. Both of these tactics have

led to court cases involving builders

and government entities. A Supreme

Court ruling in 1997 clarified that

apprenticeship programs need proper

certification at the state or federal lev-

el, which increases employer costs.14

Typically, the hiring of apprentices

or helpers still lowers wage bills,

compared with hiring journeymen.

Double-breasting by

firms permits a single

company to operate

union and nonunion

shops. “The open

shop branch of a

double-breasted firm

is supposed to be a

separate concern, with

its own offices, man-

agement, and payroll.

Unions have charged

that in many cases

these distinctions are

artificial and that the

union contract legally

applies to the non-

union subsidiary.”15

Still the practice has

spread as firms re-

spond to prevailing wages and vanish-

ing productivity advantages for union

labor. The added flexibility enables

a firm to bid for government con-

tracts under prevailing wage laws,

while also being competitive for

private contracts.

Conclusion

The labor market for the construc-

tion industry has been especially

tight after the construction boom of

the 1990s. This has resulted in wage

increases beyond those found in

other industries, departing from the

long-term trend of downward relative

wages for construction workers. How-

ever, the long-term trend suggests

continued de-skilling in the construc-

tion sector, which will lead to further

downward pressure on wages. In

view of this, the recent relative wage

gains for construction workers may

not be sustainable.

—David B. Oppedahl

Associate economist

11Michael H. Moskow, 1997, “Construction

industry wage controls during the Nixon Ad-

ministration,” paper presented before the

meeting of the Industrial Relations Research

Association, December.

2Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

3Calculated from the Bureau of Labor Statis-

tics, Current Population Survey.

4Available at http://stats.bls.gov/news.release/

wkyeng.t07.htm.

5Economic Report of the President, Feb. 2000, pp.

135-137.

6George J. Borjas, 2000, Issues in the Economics of

Immigration, University of Chicago Press, p. 6.

7Quote from Wally Randa in Matthew Power, 2000,

“Assembly required,” Builder, February, p. 67.

8Data from OSHA, available at www.bls.gov/

oshcfoi1.htm and www.bls.gov/special.requests/

ocwc/oshwc/osh/os/osnr0009.txt.

9Steven G. Allen, 1988, “Declining unionization in

construction: The facts and reasons,” Industrial

and Labor Relations Review, Vol. 41, No. 3, p. 357.

10Based on data from the Current Population Survey,

available on the Internet at http://stats.bls.gov/

news.release/union2.nws.htm.

11Albert Schwenk, 1996, “Trends in the differences

between union and nonunion workers in pay us-

ing the Employment Cost Index,” Compensation

and Working Conditions, September, pp. 27-33.

12Daniel Quinn Mills, 1972, Industrial Relations and

Manpower in Construction, MIT Press, p. 16.

13Gerald Finkel, 1997, The Economics of the Construc-

tion Industry, Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, p. 129.

14Supreme Court of the United States, 1997, No.

95-789, February 18.

15Allen, op. cit., p. 358.

Michael H. Moskow, President; William C. Hunter,

Senior Vice President and Director of Research; Douglas

Evanoff, Vice President, financial studies; Charles

Evans, Vice President, macroeconomic policy research;

Daniel Sullivan, Vice President, microeconomic policy

research; William Testa, Vice President, regional

programs and economics editor; Helen O’D. Koshy,

Editor.

Chicago Fed Letter is published monthly by the

Research Department of the Federal Reserve Bank

of Chicago. The views expressed are the authors’

and are not necessarily those of the Federal

Reserve Bank of Chicago or the Federal Reserve

System. Articles may be reprinted if the source is

credited and the Research Department is

provided with copies of the reprints.

Chicago Fed Letter is available without charge from

the Public Information Center, Federal Reserve

Bank of Chicago, P.O. Box 834, Chicago, Illinois

60690-0834, tel. 312-322-5111 or fax 312-322-5515.

Chicago Fed Letter and other Bank publications are

available on the World Wide Web at http://

www.frbchi.org.

ISSN 0895-0164

More intriguing information

1. Luce Irigaray and divine matter2. EFFICIENCY LOSS AND TRADABLE PERMITS

3. Higher education funding reforms in England: the distributional effects and the shifting balance of costs

4. THE AUTONOMOUS SYSTEMS LABORATORY

5. The name is absent

6. The name is absent

7. News Not Noise: Socially Aware Information Filtering

8. The name is absent

9. The name is absent

10. Endogenous Heterogeneity in Strategic Models: Symmetry-breaking via Strategic Substitutes and Nonconcavities