Keystone sector methodology applied to Portugal

In a social network, bigger is not always better. Increasing the network size

without considering its diversity can very often affect the quality of the social network.

If added contacts lead each node to the same people they can become redundant, which

means costly. A very dense network could be considered inefficient in the way that it

returns less diverse information with a higher cost than a less dense but diversified

network. Measuring the effort/time needed to add a new contact as an additional cost,

one actor is inefficient if the new contact leads to a similar existent contact. It is

considered as a redundancy while it only adds cost against no added gain.

To find such structural holes, empirical indicators - cohesion or structural

equivalence - are used. Two contacts are redundant “to the extent that they are

connected by a strong relationship ” (husband and wife will constitute a redundancy to

the set of a third person contacts). Two people are said to be structural equivalent “ to

the extent that they have the same contacts” (knowing one or two ministers in the same

Government). Usually cohesion is the criterion to find direct contacts and structural

equivalence is appropriate to find indirect contacts. Although they are important

indicators, they are neither absolute nor independent. When jointly considered,

redundancy is most likely to occur between structurally equivalent people connected by

a strong relationship rather than between total strangers in distant groups.

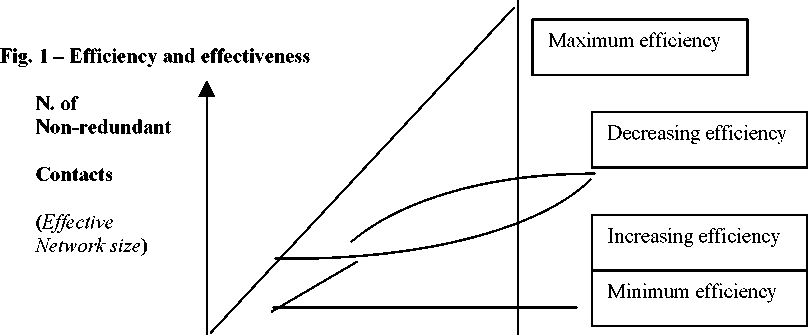

Under this perspective, balancing network size is a question of optimizing

structural holes. It is reasonable to predict that the number of structural holes will rise

with the network size, so it is important to consider the two design principles behind the

optimal network: efficiency and effectiveness.

These principles are represented in figure 1, extracted from Burt (1992: 24):

N. of contacts (Network size)

More intriguing information

1. The name is absent2. A Regional Core, Adjacent, Periphery Model for National Economic Geography Analysis

3. Strengthening civil society from the outside? Donor driven consultation and participation processes in Poverty Reduction Strategies (PRSP): the Bolivian case

4. Short- and long-term experience in pulmonary vein segmental ostial ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation*

5. APPLYING BIOSOLIDS: ISSUES FOR VIRGINIA AGRICULTURE

6. The urban sprawl dynamics: does a neural network understand the spatial logic better than a cellular automata?

7. Financial Markets and International Risk Sharing

8. Credit Markets and the Propagation of Monetary Policy Shocks

9. The name is absent

10. What Lessons for Economic Development Can We Draw from the Champagne Fairs?