theories. The most important criticism in general being that the classical spatial-economic

theories from the sixties overestimate the influence of transport costs in location decisions (for

example O’Farrell en Markham, 1975; Weisbrod et al., 1980). Nevertheless, although these

theories from the sixties are regarded to overestimate the influence of travel costs, transport

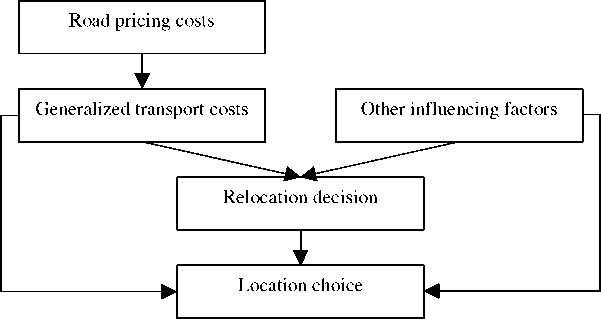

costs seem to influence location decisions to a certain extent. Besides that, road-pricing costs

make travel costs more variable, possibly leading to an even stronger connection between

generalized travel costs and location choices (figure 1) than when travel costs only consist of

fixed costs (such as for example road taxations). It follows that road pricing may play a role in

both stages of the relocation process: the decision whether or not to relocate and the choice of

the new residential location. If road pricing plays a role in the decision to relocate, it will

logically also affect the residential location choice. However, if a household chooses to

relocate for another reason, road pricing might still influence the choice of a new residential

or work location.

Figure 1: road pricing and (re)location choice

Due to relocations, spatial changes in the demand of locations may occur. These demand

shifts can also lead to changing housing prices. However, these changing prices will first of

all quite likely depend on the type of pricing measure. For example, spatial differentiated

forms of pricing may lead to higher spatial price differences than more general types of

measures. Secondly, the influence of a specific price measure on housing prices will be

dependent on the spatial characteristics of a certain region. For example, are jobs and houses

evenly spread over a region or do clear nodes exist where work and housing activities come

together? Although effects of measures on housing prices might occur, this paper will not

focus on studying these price effects.

More intriguing information

1. Language discrimination by human newborns and by cotton-top tamarin monkeys2. The name is absent

3. Estimating the Technology of Cognitive and Noncognitive Skill Formation

4. The name is absent

5. The name is absent

6. The name is absent

7. The name is absent

8. Wirkt eine Preisregulierung nur auf den Preis?: Anmerkungen zu den Wirkungen einer Preisregulierung auf das Werbevolumen

9. Fiscal Sustainability Across Government Tiers

10. Perfect Regular Equilibrium