FRANCK RAMUS

Minutes

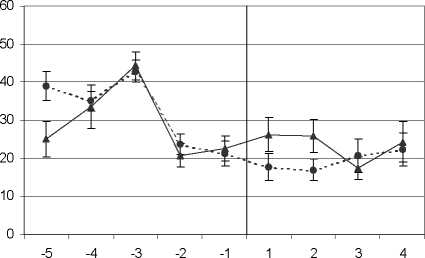

Control group —⅛— Experimental group

Figure 2. Exp. 2: Dutch-Japanese discrimination - Saltanaj

speech, first shift. Minutes are numbered from the shift, indicated

by the vertical line. Error bars represent ±1 standard error of the

mean. Adapted with permission from Ramus et al. (2000). Copy-

right 2000 American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Nevertheless, a discrimination index I was computed ac-

cording to the following formula (Hesketh et al., 1997):

I = post22eχpe - pre2eχpe) - (post2amt - pre2amt)

where post2 and pre2 refer to the average number of sucks

during the 2 post-shift (respectively pre-shift) minutes, and

where the cont and expe indices refer to the type of shift

(control or experimental). Thus, a baby increasing her sucks

more to the language shift than to a speaker shift will have a

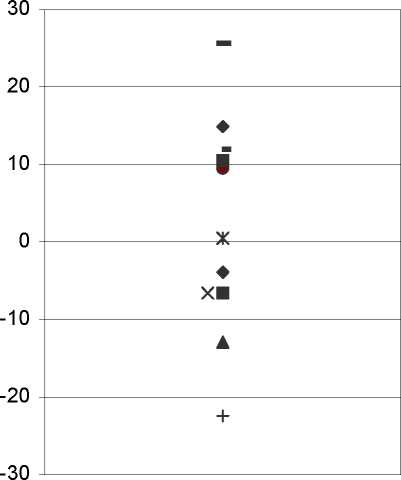

strictly positive I. Figure 3 gives the values of I for the 11

babies. Table 1 shows the dishabituation scores depending

on type and order of the shifts.

Table 1

Dishabituation scores (post2— pre2) according to order and

type of the shift. The number of observations per case is

indicated in parentheses.

|

First shift |

Second shift | |

|

control/experimental (4) |

0 |

+08 |

|

experimental/control (7) |

+6.6 |

+4.5 |

There is a very slight trend in the predicted direction: ba-

bies increase their sucking more during experimental shifts

than during the corresponding control ones. However, this

is true of 6 babies out of 11 only, and the average discrim-

ination index is 1.9 ± 14, not significantly different from 0

[t( 10) < 1].

Note that during the first shift, these 11 babies are behav-

ing consistently with the others during the first shift: they

increased their sucking more (+6.6) to the language change

than to the speaker change (+0). Thus, whereas the first shift

reveals meaningful information concerning the reactions of

infants, the second shift merely shows a perseveration of the

Figure 3. Exp. 2: Values of index I for 11 babies passing the two

shifts.

behavior produced during the first shift, which is little mod-

ulated by the nature of the second shift. In summary, this

attempt suggests that there is little to learn from a second

shift with newborns. However, this outcome does not dimin-

ish the results obtained on the first one, which are clear and

interpretable.

Discussion

The data obtained on the 32 newborns who successfully

passed the first shift show that (a) they are able to discrimi-

nate between Dutch and Japanese, (b) they can do so when

sentences are resynthesized in the saltanaj manner, i.e. when

lexical, syntactic, phonetic and most phonotactic information

is removed..

Although the interaction with Exp. 1 is not quite signifi-

cant [F(1,59) = 2.6, p = 0.11]9, this is also consistent with

the hypothesis that newborns have difficulties coping with

talker variability (Jusczyk et al., 1992), which would be the

reason why they failed to discriminate the same sentences

when they were not resynthesized.

The saltanaj resynthesis achieves a comparable level of

stimulus degradation as low-pass filtering: Since all the du-

rations and the fundamental frequency are faithfully repro-

duced, prosody, in a broad sense, is still preserved. It is

9 Note that interaction are seldom significant in experiments on

newborns anyway, due to their low statistical power. For instance,

in directly comparable studies, no significant interaction were ever

reported (Mehler et al., 1988; Nazzi et al., 1998).

More intriguing information

1. THE ANDEAN PRICE BAND SYSTEM: EFFECTS ON PRICES, PROTECTION AND PRODUCER WELFARE2. The name is absent

3. News Not Noise: Socially Aware Information Filtering

4. Why unwinding preferences is not the same as liberalisation: the case of sugar

5. The name is absent

6. The name is absent

7. The Clustering of Financial Services in London*

8. Mortality study of 18 000 patients treated with omeprazole

9. The name is absent

10. The name is absent