429

TABLE I

SELECTIVE ATTENTION: TEN EMPIRICAL

GENERALIZATIONS REFLECTING THE LITERATURE

UPTO 1986

W.A. Johnston and V.J. Dark, Ann. Rev. PsychoLi 1986, 37: 43—75.

1. All levels of stimulus analysis can be primed for

particular stimuli.

2. Selection based on sensory cues is usually superior to

selection based on semantic cues.

3. Irrelevant stimuli sometimes undergo semantic

analysis.

4. Spatial cues are especially effective cues.

5. Attention is independent of eye fixation and can assume

the characteristics of an adjustable-beam spotlight.

6. Stimuli outside the spatial focus of attention undergo

little or no semantic processing — is restricted mainly to

simple physical features.

7. Overlapping objects can be selectively processed.

8. Non-Selected objects within the spatial foci of attention

undergo little or no semantic processing.

9. Selective processing is sometimes performed passively

and sometimes actively.

10. Selective attention can be guided by active schemata.

Mirsky and Orren (1977) described 3 such spheres

— consciousness, sleep-wakefulness and orienta-

tion-habituation. Together they strongly influence

arousal, vigilance, attention and adaptive interac-

tions of the organism with the environment.

Cutting across these schemata are numerous at-

tempts to describe the functional mode of attentional

mechanisms. These account for numerous observa-

tions in terms of categories of characteristics that in

turn allow predictions for more detailed experiment.

They are thus heuristically useful but intellectually

limited by the constraint of the dichotomy they erect.

Examples include serial vs. parallel processing,

active∕passive or automatic∕controlled processes,

stimulus-∕response-set, sensory-∕concept-driven,

open-∕closed-loop or exogenous/endogenous con-

trol of processing (Straube and Oades 1992 and

references therein). Suffice it to say, in this short

overview, that one can imagine a concept-(experi-

ence)-driven selection proceeding ‘automatically’

and, depending on the demands of the situation,

involving either serial or parallel processing.

For someone setting out to investigate biologi-

to objects

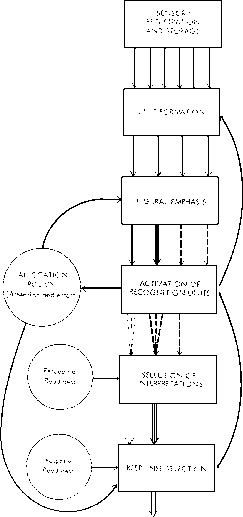

Fig. 2. Kahneman’s scheme (1973, with permission) illus-

trating interactions of perceptual mechanisms and attentional

processes.

cal measures associated with selective attention the

model elaborated now 20 years ago by Kahneman

(1973) is still useful (Fig. 2). Some advances in

ERP research can be usefully placed against the

background of this model even though it is biased

toward serial processing schemes. Thus, for ex-

ample, we can see that dimensions of a stimulus

may be processed hierarchically according to per-

ceptual difficulty, as was demonstrated with meas-

ures of processing negativity (PN), where locus in

a dichotic paradigm is processed faster than pitch

(Hansen and Hillyard 1983). But fundamental to

the design of most modern studies of selective

processes is the emphasis on the adaptive rather

than the salient aspect of the stimulus: the ability

to discriminate a stimulus that is relevant to the

More intriguing information

1. The problem of anglophone squint2. The name is absent

3. WP RR 17 - Industrial relations in the transport sector in the Netherlands

4. he Effect of Phosphorylation on the Electron Capture Dissociation of Peptide Ions

5. The name is absent

6. AMINO ACIDS SEQUENCE ANALYSIS ON COLLAGEN

7. Estimated Open Economy New Keynesian Phillips Curves for the G7

8. A Bayesian approach to analyze regional elasticities

9. Tissue Tracking Imaging for Identifying the Origin of Idiopathic Ventricular Arrhythmias: A New Role of Cardiac Ultrasound in Electrophysiology

10. The name is absent