430

organism and situation from one that is irrelevant

(Posner and Boies 1971).

NeurobioIogy of attention

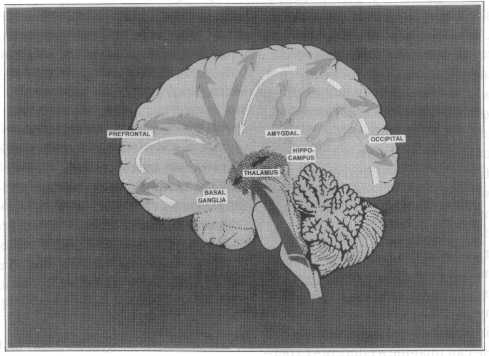

In moving from the phenomenon of attention to

the medium it is important to emphasize that the

origins of CNS-Contributions are widespread but

the component mechanisms may be more local-

ized. To see the relations between the two it is es-

sential to recall the basic anatomical basis for the

incoming flow of information. Refinements (e.g.

fronto-temporal crosstalk) or interpretations (e.g.

control diagrams) represent later developments and

are the consequences of specific experiment.

Specific sensory information ascends through

the thalamus (Fig 3). Here there are collateral links

with the non-specific nuclei mediating interven-

ing variables such as wakefulness. Information that

has gone on to association cortices may elicit a

‘gating’-like feedback at the level of the thalamus.

This type of effect is shown by ERP records (e.g.

Hackley et al. 1987) of attentional effects on com-

ponents as early as 20 msec. The anatomical links

for feedback may be remarkably specific: Siwek

and Pandya (1991) showed links between small

sub-groups of cells in prefrontal and mediodorsal

thalamic areas, (e.g. area 9, 10 with the most dor-

sal part of the nucleus).

As the Pl∕P50 is usually accepted as reflecting

the passage from thalamus to the relevant primary

cortices and N !-associated components, the sub-

sequent distribution to appropriate associative ar-

eas (Knight et al. 1988), we should note two

striking findings at this level in schizophrenia.

The first concerns prepulse inhibition (PPI). The

normal ability of a soft sound to interfere with fur-

ther processing of a loud noise c. IOO msec later,

as indexed by the P50, is reduced in schizophren-

ics. Even though the size of the basic startle effect

may depend on DA activity, the tuning effect in-

volved here is normally associated with decreased

NA activity (see below). A schizophrenic group

studied by Waldo et al. (1992) did not modulate

their NA activity. PPI is usually reduced in acute

psychosis (including mania), but not in obsessive-

compulsive disorder (Schall et al. submitted).

The second confirms that the areas and connec-

tions active at the P50-Nl latency can function

Fig. 3. Illustration of the flow of sensory events through several stages of processing in the brain: note-, 1, ascent through the

thalamus (collateral interaction) to primary sensory cortices; 2, allocation to association cortices (potential for feedback con-

trol); 3, subcortical loops (e.g. basal ganglia, thalamus, amygdala, hippocampal complex); modulation by long-axon ascending

aminergic systems (e.g. DA, NA, 5HT. ACh) not shown.

More intriguing information

1. Strategic monetary policy in a monetary union with non-atomistic wage setters2. The name is absent

3. What Contribution Can Residential Field Courses Make to the Education of 11-14 Year-olds?

4. Change in firm population and spatial variations: The case of Turkey

5. Innovation Policy and the Economy, Volume 11

6. The name is absent

7. EU enlargement and environmental policy

8. Outsourcing, Complementary Innovations and Growth

9. PER UNIT COSTS TO OWN AND OPERATE FARM MACHINERY

10. Do the Largest Firms Grow the Fastest? The Case of U.S. Dairies