Gerontocracy in Motion?

17

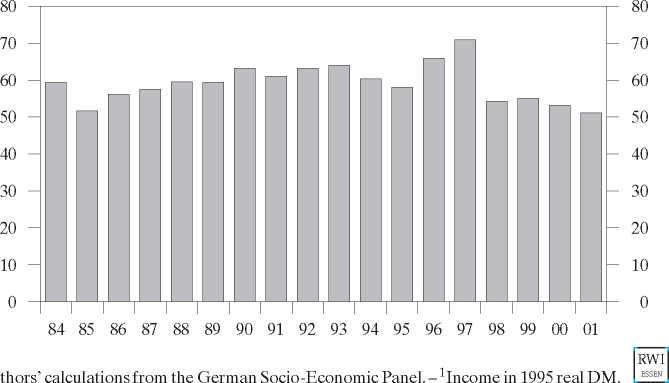

Figure 5

Relative Income1 of Full-Time Working 18-21 Year Olds in Germany

1984-2001; % of income of rest of workers

work without significant frictions (see below), the relative wages of younger

cohorts will rise. Since labor income is the principal income source for most in-

dividuals and families, these altered age-earnings or age-wage profiles then

translate into a higher per-capita income in the young generation.

As an empirical point of departure, this focus on relative changes of labor sup-

ply across different age groups calls for an augmentation of standard wage re-

gressions with measures of current cohort sizes. A large body of literature ana-

lyzing the US baby boom cohorts (e.g. Connelly 1986; Freeman 1979; Welch

1979) already documents a corresponding response of wages to a relative shift

in labor supply, with larger cohorts experiencing lower wages. The empirical

evidence for European countries is rather slim, though, and no clear picture

emerges. Wright (1991) provides evidence for the case of UK that larger co-

horts have lower earnings, when they are young but that this effect does not

persist as the cohort ages. Klevmarken (1993) reports no significant cohort

size effects for Swedish data. However, Dahlberg/Nahum (2003), utilizing al-

ternative data for the case of Sweden, find significant effects of cohort sizes on

earnings. According to their results, these estimated effects vary across educa-

tion levels.

For Germany, despite the rather strong decline in birth rates in the 1970s and

the corresponding decline in relative cohort sizes of the young, no obvious ef-

fect on the relative income position of younger cohorts emerges (Figure 5).

More intriguing information

1. The name is absent2. The Determinants of Individual Trade Policy Preferences: International Survey Evidence

3. The InnoRegio-program: a new way to promote regional innovation networks - empirical results of the complementary research -

4. The name is absent

5. Financial Development and Sectoral Output Growth in 19th Century Germany

6. The voluntary welfare associations in Germany: An overview

7. Antidote Stocking at Hospitals in North Palestine

8. Global Excess Liquidity and House Prices - A VAR Analysis for OECD Countries

9. The name is absent

10. Parallel and overlapping Human Immunodeficiency Virus, Hepatitis B and C virus Infections among pregnant women in the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja, Nigeria