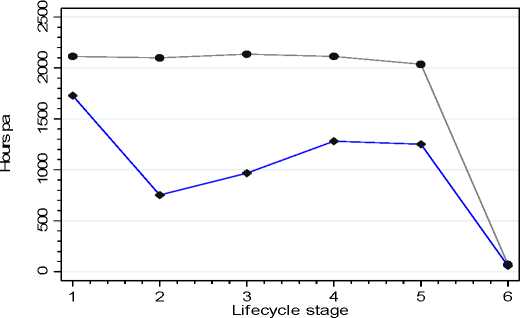

Figure 3: Labour supply by gender

Males -- -- Females

male labour supply. Although female hours then tend to rise in the following working-

age phases, they do not reach much above 50 per cent of male hours, even after the

children have left home in phase 5.

Time use data show that the sharp fall in female hours in phase 2 is associated with an

even more dramatic rise in hours of domestic work, much of which is childcare.24

This suggests that, due to the demand for childcare, domestic work is a close

substitute for market work in this phase. The data offer an explanation for why the

labour supply elasticity of the female partner, typically on a lower wage, is found to

be greater than that of the male partner, especially in a country with a poorly

developed childcare sector. When market and home childcare are close substitutes,

and childcare is costly, tax rates on the income of married mothers at the levels

indicated in the preceding section can be expected to induce labour supply responses

that generate low female hours as depicted in Figure 3.

The average profile for female labour supply in Figure 3 conceals the high degree of

heterogeneity observed in female hours. The majority of married women work either

24 See Apps and Rees (2005). Time use data for a number of countries, including the UK, US and

Germany, as well as the 1997 ABS Time Use Survey data, show this.

13

More intriguing information

1. The name is absent2. The name is absent

3. Natural Resources: Curse or Blessing?

4. The name is absent

5. The Role of State Trading Enterprises and Their Impact on Agricultural Development and Economic Growth in Developing Countries

6. Surveying the welfare state: challenges, policy development and causes of resilience

7. The name is absent

8. The name is absent

9. Multi-Agent System Interaction in Integrated SCM

10. INTERACTION EFFECTS OF PROMOTION, RESEARCH, AND PRICE SUPPORT PROGRAMS FOR U.S. COTTON