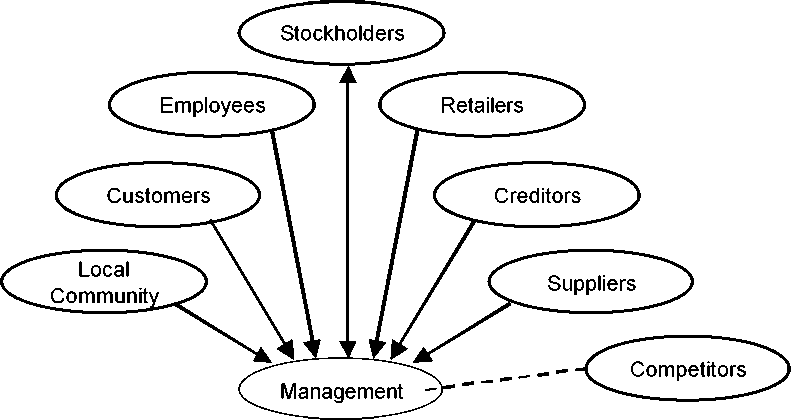

Figure 2: Stakeholder Theory

The stakeholder role advocates responsibility to all of the interest groups and only to these interest

groups. It does not advocate that the manager act in the best interests of society. This is vague and may

lead to arbitrary actions. For example, assume that General Motors donated money to the University of

Pennsylvania. Under the stakeholder role, such a contribution would be regarded as irresponsible since

the university would hardly be considered as one of General Motors’ interest groups. (In this case, the

burden of proof would be on the management of G.M. to show that the donation was a good

“investment” for its primary stakeholders.) Incidentally, although both the stakeholder and the

stockholder roles [23,35] are in agreement that charitable donations are irresponsible, they are legal in

the U.S., having survived a legal challenge [7].

From the previous definitions of social irresponsibility, it seems that managers who follow the

stakeholder role would not act irresponsibly. The question is how to get managers to adopt such a role.

Although the stakeholder role was discussed at least 40 years ago [ 17, 18], there has been little

movement in this direction. For example, “Campaign GM,” an effort to place consumer and community

representatives on the General Motors board of directors, received only about 3% of the stockholders’

votes [61].

The Panalba Role-Playing Experiment

Validity of Role-Playing: Survey research presents a number of difficulties in the study of social

irresponsibility. Respondents describe themselves in a favorable light. Furthermore, they often have

difficulty in deciding how they would respond in various situations. On the other hand, field experiments

on irresponsibility are expensive and difficult to arrange, and subjects can also become upset in field

experiments (e.g., the nurses in the Hofling et al. [28] study were upset when they found that they were

the subjects of an experiment).

More intriguing information

1. Nonparametric cointegration analysis2. A Unified Model For Developmental Robotics

3. THE WAEA -- WHICH NICHE IN THE PROFESSION?

4. Les freins culturels à l'adoption des IFRS en Europe : une analyse du cas français

5. Has Competition in the Japanese Banking Sector Improved?

6. The name is absent

7. Dual Inflation Under the Currency Board: The Challenges of Bulgarian EU Accession

8. Education Responses to Climate Change and Quality: Two Parts of the Same Agenda?

9. Short report "About a rare cause of primary hyperparathyroidism"

10. Telecommuting and environmental policy - lessons from the Ecommute program