1234

V-V units

1 2345

V-V units

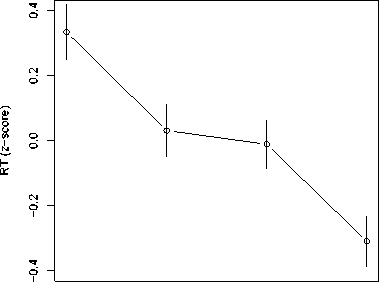

Figure 3: Normalized RT for click detection along positions in

stress groups of four V-to-V units. Whiskers indicate standard

error.

faster it is attended to. It means that perception facilitation is

somehow a function of time, what can be seen as a preliminary

evidence that question (2) can also have a positive answer.

The issue to be settled now is whether time is to be inter-

preted just as order (V-to-V position in stress group) or if the

perceptual entrainment is related to actual produced timing. In

order to tackle this problem, duration and RT data were corre-

lated.

Mean V-to-V duration of the four V-to-V units of the eight

sentences in group (A) were correlated to the corresponding

normalized RT means. The best correlation was achieved

through non-linear estimation using a polynomial function like

y = a + bx + cx2 yielding r = -0.764 (p < 0.009). Duration

data explain 58% of RT variance in this case.

As for group (B), means of position 1 to 3 were pooled over

and so were means of position 4 and 5 as suggested by Scheffe

homogeneous groups test. RT means were pooled over the same

way. Likewise group (A), the best correlation was the one we

got through non-linear estimation using the same function. In

this case r = -0.77 (p < 0.002) and a proportion of 59% of

RT variance can be accounted for by duration data.

4. Discussion

Correlation results seem to represent preliminary evidence that

speech perception and production patterns can in fact be closely

related, since almost 60% ofRT variance in the experiment can

be traced back to duration scaffolding in production. Future ex-

periments are to show if correlates of intonation play any role

in predicting perception. Besides that, they should also investi-

gate how semantic information helps listeners predict when and

where speakers will place stress along a sentence.

5. Acknowledgements

This work was supported by FAPESP grants 03/11619-0 and

05/02525-7. We thank Luciana Lucente and Sandra Madureira

for their help with intonational labelling.

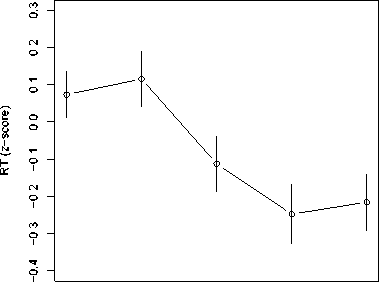

Figure 4: Normalized RT for click detection along positions in

stress groups of five V-to-V units. Whiskers indicate standard

error.

6. References

[1] Collischonn, G., 1994. Acento secundario em portugues

brasileiro. Letras de Hoje, 29, 43-53.

[2] Said Ali, M., 1908. Difficuldades da Lingua Portugueza:

Estudos e Observacoes. Rio de Janeiro: Laemmert.

[3] Moraes, J. A., 2003. Secondary stress in Brazilian Por-

tuguese: perceptual and acoustical evidence. In Proceed-

ings of the 15th ICPhS. Barcelona, Spain, 2063-2066.

[4] Prieto, P.; van Santen, J., 1999. Secondary stress in Span-

ish: some experimental evidence. In Aspects of Romance

Linguistics. C. Parodi et al. (eds.). Washington: GUP, 337-

356.

[5] Barbosa, P. A.; Arantes, P.; Silveira, L. S., 2004. Unify-

ing stress shift and secondary stress phenomena with a

dynamical systems rhythm rule. In Proceedings Speech

Prosody 2004, Nara, Japan, 49-52.

[6] Barbosa, P. A., 2002. Explaning cross-linguistic rhytmic

variability via a coupled-oscillator model of rhythmic pro-

duction. In Proceedings of Speech Prosody 2002. Aix-en-

Provence, France, 163-166.

[7] Barbosa, P. A.; Bailly, G. 1994. Characterisation of rhyth-

mic patterns for text-to-speech synthesis. Speech Commu-

nication, 15: 127-137.

[8] Cutler, A.; Foss, D. N., 1977. The role of sentence stress in

sentence processing. Language and Speech, 20(1), 1-10.

[9] Martin, J. G., 1972. Rhythmic (hierarquical) versus ser-

ial structure in speech and other behavior. Psychological

Review, 79(6), 487-509.

[10] Quene, H.; Port, R. F., 2005. Effects of timing regular-

ity and metrical expectancy on spoken-word perception.

Phonetica, 62(1), 1-13.

[11] Large, E. W.; Jones, M. R., 1999. The Dynamics of At-

tending: How People Track Time-Varying Events. Psy-

chological Review, 106(1), 119-159.

More intriguing information

1. Modelling Transport in an Interregional General Equilibrium Model with Externalities2. The name is absent

3. Improving the Impact of Market Reform on Agricultural Productivity in Africa: How Institutional Design Makes a Difference

4. The name is absent

5. The name is absent

6. BILL 187 - THE AGRICULTURAL EMPLOYEES PROTECTION ACT: A SPECIAL REPORT

7. Developmental changes in the theta response system: a single sweep analysis

8. The name is absent

9. The name is absent

10. The name is absent