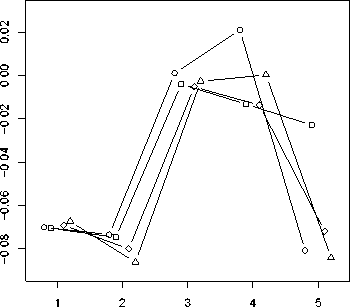

V-V units

Figure 1: Normalized duration in stress groups containing four

syllable words. Point markers stand for different values of dσ.

◦ is 0, □ is 2, O is 3 and △ is 4.

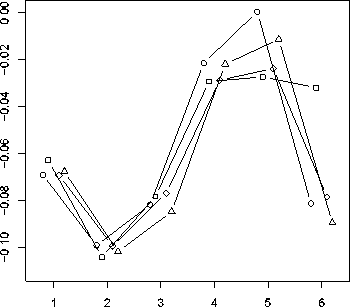

V-V units

Figure 2: Normalized duration in stress groups containing five

syllable words. Point markers stand for different values of dσ .

◦ is 0, □ is 2, O is 3 and △ is 4

cal factors and mean normalized duration as dependent vari-

able, an ANOVA carried on the group of four-syllable words

yields significance only for the position factor (F (2, 1305) =

456.06, p < 10-4), although positions 1 and 2 are not statis-

tically different as pointed out by a Scheffe post-hoc test. A α

level of5% was adopted.

As for the five-syllable words group, only the position fac-

tor yields significance (F (3, 1144) = 124.3, p < 10-4).

Here, positions 1 and 2 are statistically different, according to

Scheffe test (p < 0.003 for dσ = 2 and p < 0.04 for dσ = 4).

These results are evidence for a gradient lengthening of the first

V-to-V unit as the stress group gets longer, due to longer target

words or the presence of an adjective (dσ = 4). No evidence

for binary alternations shows up.

2.2. Intonational Patterns

A set of f0 contour samples from our corpus was examined

and labeled with the help of three phoneticians. In the agreed

transcription, a H* tone is associated to the first syllable of the

target words, irrespective of its length. A complex tone H*+L

orL*+H is associated with the lexically stressed syllable of the

target.

Future work on BP intonation will show if pitch accents

should be expected in initial position in circumstances other

than those involving stress groups starting with polysyllabic

words.

2.3. Summing up

It’s difficult to see how the results, taken together, can be ac-

counted for by metrical-like representations. Timing and into-

national patterns suggest that the initial prominence is related

to prosodic phrasing rather than to a hierarchical relation estab-

lished with the lexically stressed syllable. It seems more appro-

priate to consider this subordinate prominence as a stress group

initial strengthening. Support for this interpretation comes from

the fact that initial lengthening can be generated by the rhythm

production model [6]. Follow-up studies should investigate how

the pattern of prominence(s) along prestressed syllables is af-

fected by (a) target word position within sentence and (b) se-

mantic factors like referential status (i.e., if target word is given

or new information).

3. Perception Study

Duration contours elicited in our production study are highly

constrained. The shape of change in duration that culminates

in a phrasal stress follows a pattern that can be successfully ac-

counted for by the model described in [6]. Given this fact, the

following questions can be raised: (1) since prosody is a trade-

off between speakers’ and listeners’ needs, then listeners’ per-

ception of such stimuli are in some way constrained? (2) If so,

is this pattern related to the one we find in production?

There has been some positive answers to question (1). It

has been found that when a word carries sentence stress its per-

ception is somehow facilitated [8] [9]. This finding has been

brought to light by having subjects responding to word-initial

phoneme targets on stressed and unstressed words and it came

out that reaction time (henceforth RT) speeds up when the target

phoneme is in a stressed position. The claim is that in every sen-

tence there are points which catch listeners’ attention. There-

fore, words in those spots are more accurately processed. It has

been also demonstrated [10] that in word lists where timing was

carefully manipulated so that stressed syllables seemed to occur

at periodic points in time, RT to target phonemes were shorter

when compared to a situation where some jitter was introduced

in the timing of stressed syllables. It seems thus clear that lis-

teners can benefit from rhythmically patterned stimuli.

These experiments cannot state, however, if the effects

of timing are local to the rhythmically crucial spots or if

these spots are actively exploited all over the stimuli. Studies

by experimental psychologists on how people attend to time-

changing stimulus [11] suggest the latter option is likely to be

true. To put forward the idea that speech perception and pro-

duction constrain each other is a way to start answering ques-

tion (2). The hypothesis stated here is that it can be expected

that listeners’ attention is actively entrained by speakers’ ac-

More intriguing information

1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY2. The Interest Rate-Exchange Rate Link in the Mexican Float

3. Initial Public Offerings and Venture Capital in Germany

4. The name is absent

5. 5th and 8th grade pupils’ and teachers’ perceptions of the relationships between teaching methods, classroom ethos, and positive affective attitudes towards learning mathematics in Japan

6. Factores de alteração da composição da Despesa Pública: o caso norte-americano

7. Implementation of the Ordinal Shapley Value for a three-agent economy

8. Sex differences in the structure and stability of children’s playground social networks and their overlap with friendship relations

9. The name is absent

10. Target Acquisition in Multiscale Electronic Worlds