fundamental role that material symbols and images play in the context of religion and

ritual. Yet it is this argument that formulates the conceptual basis from which Mithen’s

answer derives. For indeed there is a ‘second, and perhaps far more significant, way in

Animism

Material Culture

Transcendental stance

(TPJ)

Autoscopic

Phenomena

(AG)

Metaphor

(mPFC) ʌ

Theory of Mind

ToM

Anthropomorphism

. Fetishism

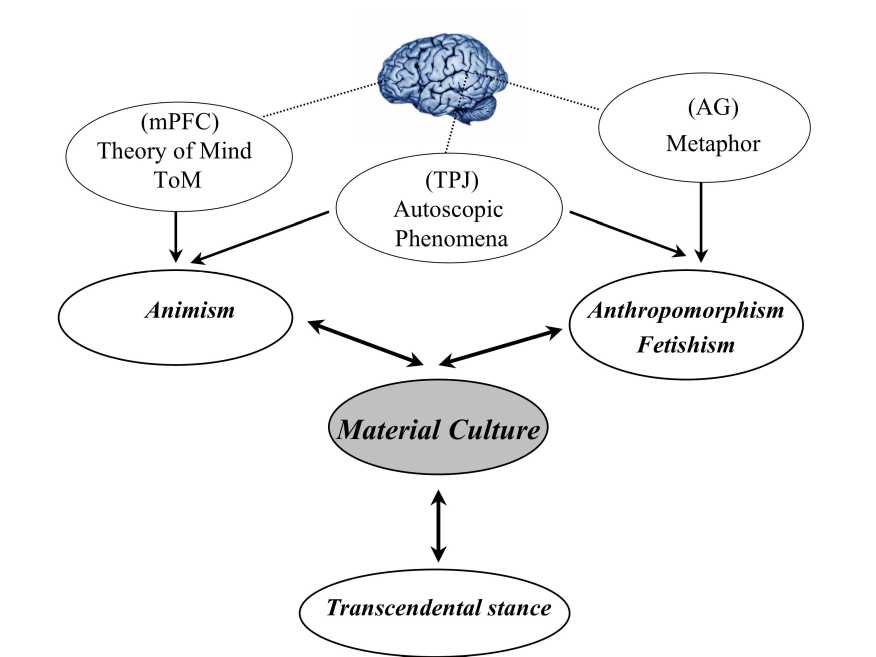

Figure 26.3. The neuro-cultural matrix active at the origin of ‘religious intelligence’.

which religious ideas are anchored’ and through which they gain extra survival value:

‘they are represented in material form’ (1998a, 103). I call this ‘second order anchoring

argument’. Obviously for Mithen the reason why religion needs material culture is

essentially to overcome the limits that biological memory imposes on the process of

religious transmission. Religious concepts and ideologies needed to be externalised in

material form so that they can be effectively remembered. This is a part of the process

that Mithen describes elsewhere as the ‘disembodiment of mind into material culture’

(1998b). Naturally, the mnemonic significance of the image is not to be disputed. I

believe however, that the general argument from memory (see also McCauley and

Lawson, 2002), although powerful, suffers from a very important shortcoming: it fails to

provide an adequate explanation for how religious ideas emerge in the first place.

Take for instance our example of the 30,000-year-old Hohenstein-Stadel lion-man

statuette. The first question that this object, of what we might term ‘hybrid-type’ imagery,

raises is how such a strange creature - half lion and half man - could have originated in

the image-maker’s imagination? According to Mithen’s argument our question, as stated

above, poses no real problems. The cognitively fluid mind has no problem imagining and

inventing concepts and creatures that violate our intuitive knowledge of the world. The

More intriguing information

1. The name is absent2. The name is absent

3. The name is absent

4. Innovation in commercialization of pelagic fish: the example of "Srdela Snack" Franchise

5. The name is absent

6. The InnoRegio-program: a new way to promote regional innovation networks - empirical results of the complementary research -

7. The name is absent

8. Foreign direct investment in the Indian telecommunications sector

9. The Formation of Wenzhou Footwear Clusters: How Were the Entry Barriers Overcome?

10. The name is absent