Aggregate Wage Flexibility in Selected New EU Member States 19

No significant wage adjustment was found for Hungary during 1992-1999. Covering a larger set

of countries over the period 1993-2003, von Hagen and Traistaru-Siedschlag (2005) obtain

regional wage elasticity of -0.15 for the Baltic countries, -0.06 for Slovakia, insignificant for the

Czech Republic and Poland, and even positive for Hungary (0.15) and Slovenia (0.56) which

indicates a sort of hysteresis (regions with higher unemployment are characterized by higher

wages, the phenomenon known as “compensating differential”). Summarizing, wage flexibility at

the regional level in the eight East European NMS does not appear to be higher than in other

developed nations.

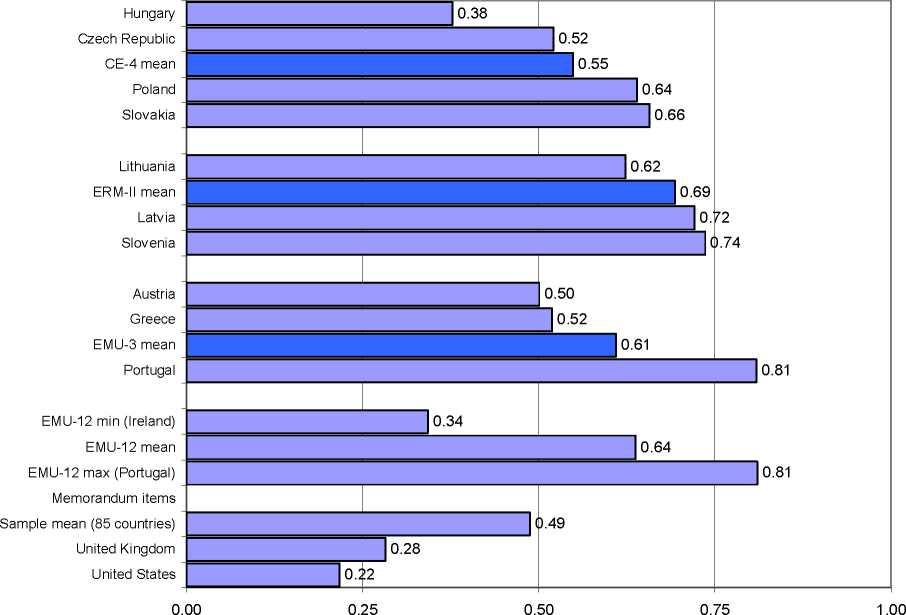

A complementary comparison of wage flexibility across countries could be done based on

institutional characteristics of labor markets. Botero et al. (2004) construct aggregate indices of

labor market rigidity (“regulation of labor”) across 85 industrialized and developing countries for

the late 1990s. The underlying indicator of protection of employed workers is the closest proxy

for micro-economic wage flexibility. Indeed, this indicator is based on assessing the cost of

increasing hours worked and the cost of firing, and it takes into account dismissal procedures and

alternative employment contract practices. These characteristics are determinants of the

(downward) wage flexibility at the microeconomic level, since the more protected workers are,

the less willing they are to accept wage decreases.

Figure 5: Indices of Labor Market Rigidity (0-low, 1-high)

Source: Botero et al. (2004)

Note: Higher indices mean higher labor market rigidity.

Figure 5 illustrates indices of labor market rigidity. The data are available for all the countries of

our sample except Estonia. Overall, the CE-4, the ERM-II participants and the EMU-3 have quite

high rigidities of comparable magnitude (the corresponding averages are 0.55, 0.69, and 0.61),

More intriguing information

1. Non-farm businesses local economic integration level: the case of six Portuguese small and medium-sized Markettowns• - a sector approach2. Examining Variations of Prominent Features in Genre Classification

3. Smith and Rawls Share a Room

4. The name is absent

5. The Clustering of Financial Services in London*

6. Midwest prospects and the new economy

7. Managing Human Resources in Higher Education: The Implications of a Diversifying Workforce

8. Word searches: on the use of verbal and non-verbal resources during classroom talk

9. Policy Formulation, Implementation and Feedback in EU Merger Control

10. Sex-gender-sexuality: how sex, gender, and sexuality constellations are constituted in secondary schools