30

20

10

À. ---- CEEC

K ' ---Kazakhstan

K K ....... Kyrgyz Republic

---Tajikistan

--Turkmenistan

1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006

Year

Source: IMF (2008).

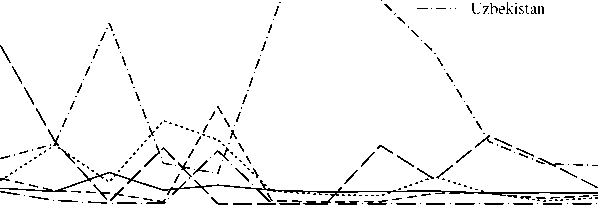

Fig. 6: Exchange Rate Volatility 1995 - 2006

in year t respectively. The minimum volatility is chosen in order to identify the manipulated,

policy relevant exchange rate. Annual figures are calculated from monthly data for each year.

Figure 6 shows that the CEECs have constantly kept their exchange rate volatilities at very

low levels while most Central Asian countries show higher volatility between 1995 and the year

2000. However, after that, Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, and Tajikistan have converged to

CEEC levels in terms of volatility. Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan show higher volatility even

after 2000, which maybe is a result of their poor institutional performance. Thus, credibility in

economic policy making can be crucial in avoiding speculative attacks on the country’s currency

or unnecessarily high exchange rate volatility which also harms external trade and long-term

capital flows.

While the incentive of financial openness in combination with fixed exchange rate regimes

consists in preventing an economic crisis, economic crises themselves can have a positive effect

in the long-run despite painful short-run effects. As already discussed in the previous section,

preferences are often shaped by historical events. Periods of systematic instability can shift

preferences in favour of better regulations among the population and policy makers and open

a window of opportunity for reforms as they reveal weaknesses in institutional arrangements

(Acemoglu and Robinson, 2001; Briickner and Ciccone, 2008). In the aftermath of the crisis

agents may have a higher willingness to reform and prefer better institutions in order to avoid

13

More intriguing information

1. Regulation of the Electricity Industry in Bolivia: Its Impact on Access to the Poor, Prices and Quality2. The name is absent

3. GOVERNANÇA E MECANISMOS DE CONTROLE SOCIAL EM REDES ORGANIZACIONAIS

4. Determinants of U.S. Textile and Apparel Import Trade

5. The Making of Cultural Policy: A European Perspective

6. Getting the practical teaching element right: A guide for literacy, numeracy and ESOL teacher educators

7. Lumpy Investment, Sectoral Propagation, and Business Cycles

8. An Intertemporal Benchmark Model for Turkey’s Current Account

9. The name is absent

10. Menarchial Age of Secondary School Girls in Urban and Rural Areas of Rivers State, Nigeria