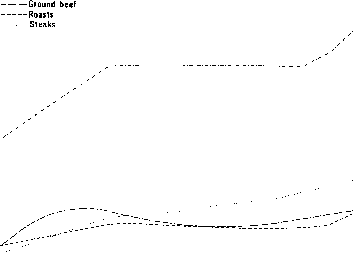

In terms of income-expenditure relationships

for fresh beef and selected types of beef, the es-

timated relations are depicted in Figure 1. For a

household size of three, Figure 1 indicates that

the patterns of fresh beef expenditure in response

to income differ among income levels. For

example, household expenditures for fresh beef

increases rather rapidly as income increases from

$2,000 to $10,000, remains quite constant be-

tween the range of $10,000 and $24,000, and

again increases as household income increases

above $24,000 (Figure 1). Furthermore, the t-test

indicates that, for fresh beef expenditure, the

linear segments are statistically significant at

either the 0.05- or the 0.Ю-significance levels,

suggesting that the slopes are different among the

various income levels (Table 1). This implies that

the marginal propensity to consume is much

higher for the low- and high-income households,

as compared with the middle-income households

in the case of fresh beef.

220

200

180

160

- 140

ɪ 120

1 wo

uj 80

60

40

20

0' 2 4 6 8 10 12 Î4 16 18 20 22 24 26 28 30

Household Income (1,000 dollars)

FIGURE 1. Beef Expenditures as a Function of

Household Income (Household Size = 3)

The estimated income-expenditure relation-

ships also reveal a sharp contrast in the expendi-

ture patterns among ground beef, beef roasts,

and beef steaks (Figure 1). Household food ex-

penditure for ground beef reaches a maximum

approximately at the income level of $8,000 and

then gradually declines as income further in-

creases. Even though the ground beef expendi-

ture curve tends to rise slightly toward the higher

income levels, this pattern does not seem to be

significant. In general, expenditure for beef

roasts resembles the ground beef expenditure

pattern except for absolute magnitude differ-

ences. Nevertheless, a significant structural

change, unlike that of ground beef, is found at the

higher level of household income. In contrast to

ground beef and beef roasts, the expenditure

curve for beef steaks shows a steadily increasing

pattern as household income increases. Similar

to beef roasts, expenditure for beef steaks re-

flects a significant structural change when

household income approaches the $25,000 level.

In summation, the results clearly suggest that

beef purchasing behavior changes as household

income increases. Households with lower in-

come tend to spend more of their food dollars for

ground beef, with no appreciable difference be-

tween beef roasts and beef steaks. As income

increases, expenditures for beef steaks increase

over the income range, with some evidence that

expenditures for ground beef decline over the

middle-income levels. Hence, for the higher in-

come families, a greater proportion of beef ex-

penditures was spent for beef steaks, with no ap-

parent difference between ground beef and beef

roasts. More specifically, the results suggest that

different beef expenditure patterns emerge as

household income changes. This implies that

over the range of the lower incomes ($2,000-

$10,000), household food expenditures for beef

steaks and beef roasts are of about the same

magnitudes at each income level. However, as

income increases above the low-income levels,

household food expenditures for beef steaks are

greater than for beef roasts and ground beef,

which are of similar magnitudes at income levels

above $10,000.

CONCLUSION

This paper demonstrates the application of

spline functions to income-expenditure relation-

ships, using household food purchase data from a

consumer panel of approximately 120 families.

The use of standard regression procedures pro-

vides flexibility and convenience in the estima-

tion of spline functions. More important, the use

of spline functions to approximate behaviorally

determined income-expenditure relations illus-

trates that various beef expenditure patterns of

structural differences can be investigated without

sample stratifications.

The results of this analysis indicate a unique

expenditure pattern for each type of beef. Spline

functions, as an approximation for estimating

income-expenditure relations, provided a proce-

dure that showed that consumers react differ-

ently to an income increase at the low-income

level than to an income increase at the higher

income level. The analysis indicates that, as ex-

penditures for beef change with increased in-

come, the mix of the household’s beef expendi-

tures also changes. Thus, expenditure for ground

beef was found to be predominant in the low-

income households, increasing rapidly as income

increased to about the $8,000 level. In contrast to

ground beef, expenditure for beef steaks was

more responsive and predominant in the high-

income households. Moreover, the results of this

study suggest that the relative importance of in-

109

More intriguing information

1. Can a Robot Hear Music? Can a Robot Dance? Can a Robot Tell What it Knows or Intends to Do? Can it Feel Pride or Shame in Company?2. Estimating the Economic Value of Specific Characteristics Associated with Angus Bulls Sold at Auction

3. Fiscal Rules, Fiscal Institutions, and Fiscal Performance

4. he Virtual Playground: an Educational Virtual Reality Environment for Evaluating Interactivity and Conceptual Learning

5. Bridging Micro- and Macro-Analyses of the EU Sugar Program: Methods and Insights

6. Reversal of Fortune: Macroeconomic Policy, International Finance, and Banking in Japan

7. Biologically inspired distributed machine cognition: a new formal approach to hyperparallel computation

8. Do the Largest Firms Grow the Fastest? The Case of U.S. Dairies

9. The name is absent

10. Parent child interaction in Nigerian families: conversation analysis, context and culture