Table 2. Gross and net debt development

|

Gross debt |

Net debt |

Change in | ||

|

Gross debt |

Net debt | |||

|

2005 |

2005 |

1993 |

2005 | |

|

Nordic model | ||||

|

Sweden |

61 |

-6 |

-18 |

-16 |

|

Finland |

48 |

-41 |

-4 |

-24 |

|

Denmark |

48 |

2 |

-11 |

-23 |

|

Netherlands |

66 |

-28 |

-32 |

-7 |

|

Austria |

65 |

39 |

3 |

-2 |

|

Anglo-Saxon model | ||||

|

United Kingdom |

46 |

39 |

-3 |

6 |

|

Ireland |

30 |

.. |

-65 |

.. |

|

Portugal |

78 |

46 |

01 |

201 |

|

Continental model | ||||

|

Germany |

72 |

61 |

24 |

33 |

|

France |

74 |

45 |

22 |

17 |

|

Belgium |

100 |

90 |

-45 |

-38 |

|

Mediterranean model | ||||

|

Italy |

121 |

98 |

-51 |

-31 |

|

Spain |

53 |

31 |

-14 |

-10 |

|

Greece |

108 |

.. |

-2 |

.. |

1. 1995-2005

Source: OECD, Economic Outlook No. 77 database.

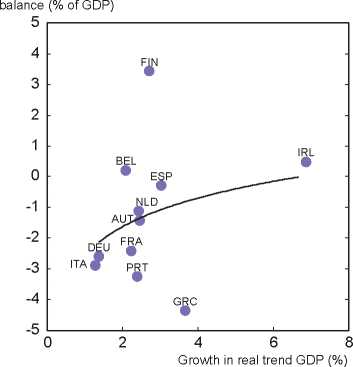

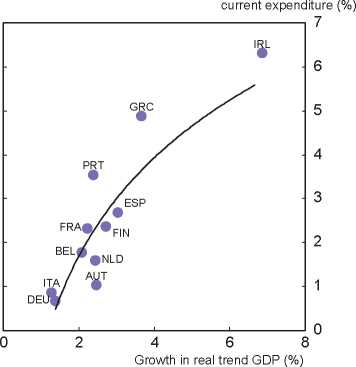

16. A similar pattern emerges when looking at growth performance and fiscal policy (Figure 4). In

the period 1999-2005, trend growth was only 1½ per cent per year on average in the three major euro area

countries, but 3¼ per cent in the smaller countries. Faster growth coincides with a strong fiscal

performance, while the contrary tends to be true for the slower-growing countries. Econometric work

provides evidence that fiscal consolidations are more likely to be undertaken and successful if trend

economic growth is high (von Hagen, 2002). At the same time, the smaller fast growing-economies were

able to maintain fairly rapid growth in public spending while keeping their government deficits in check.

Greece is of course an important exception with soaring spending and a whopping government deficit

despite strong growth.

1999-2005

Cyclically-adjusted

Source: OECD, Economic Outlook No. 77 database.

Figure 4. Trend growth and fiscal policy

average

Growth in real

50

More intriguing information

1. Commuting in multinodal urban systems: An empirical comparison of three alternative models2. Word Sense Disambiguation by Web Mining for Word Co-occurrence Probabilities

3. The name is absent

4. The name is absent

5. Insurance within the firm

6. The voluntary welfare associations in Germany: An overview

7. The name is absent

8. Personal Experience: A Most Vicious and Limited Circle!? On the Role of Entrepreneurial Experience for Firm Survival

9. Strategic Policy Options to Improve Irrigation Water Allocation Efficiency: Analysis on Egypt and Morocco

10. Industrial districts, innovation and I-district effect: territory or industrial specialization?