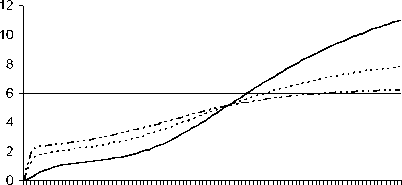

As can be seen from the following figures, there is indeed a level increase of GDP, however this is

mostly explained by the increase in employment. Additional effects from increased capital

accumulation only arrive gradually. Over the first 15 to 20 years, the transition does not lead to

additional savings.

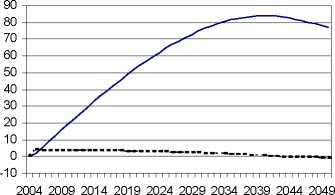

Figure 4: Partial Move to a Funded System

Debt and Deficit to GDP ratio

-------Debt to GDP ratio------Deficit to GDP rati<

Employment, GDP and Capital

2004 2013 2022 2031 2040 2049 2058 2067 2076 2085 2094

Employment GDP ------Capital

5. Conclusions

This paper has provided a projection on the likely macroeconomic impact of leaving the current

PAYG system in place and has analysed a number of alternative strategies of avoiding an increase

in non-wage labour costs. Special emphasis was laid on the question whether a partial move to a

funded system could be a feasible option from a budgetary perspective under the constraint that

age cohorts older than 40 must be subsidized by the general public over a transition period. At

least for the transition as outlined in this paper, the fiscal costs appear to be rather large and hardly

feasible from a budgetary perspective.

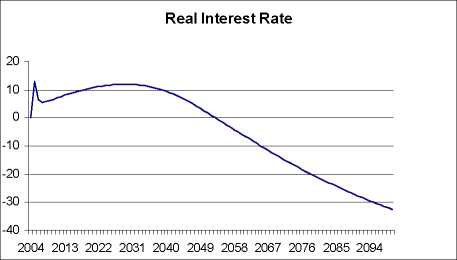

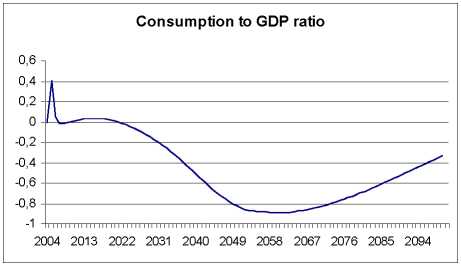

Apart from the generosity in which older worker cohorts are compensated, the crucial question is,

what are the real growth effects of such a reform and what is happening to growth of the tax base.

In this paper it is found that the macroeconomic benefits from a transition to a funded system are

limited, initially because the build up of government debt is crowding out private investment

activities. Higher savings occur in the longer term. However, in an ageing open economy it is

likely that a substantial fraction of savings will be invested abroad. The question arises whether it

will be possible to tax the returns from foreign assets.

86

More intriguing information

1. Measuring Semantic Similarity by Latent Relational Analysis2. Announcement effects of convertible bond loans versus warrant-bond loans: An empirical analysis for the Dutch market

3. Proceedings of the Fourth International Workshop on Epigenetic Robotics

4. INSTITUTIONS AND PRICE TRANSMISSION IN THE VIETNAMESE HOG MARKET

5. The name is absent

6. Studies on association of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi with gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus and its effect on improvement of sorghum bicolor (L.)

7. Detecting Multiple Breaks in Financial Market Volatility Dynamics

8. The name is absent

9. The name is absent

10. Gerontocracy in Motion? – European Cross-Country Evidence on the Labor Market Consequences of Population Ageing