number of such articles, then the fraction of extant knowledge known by an individual would

decline at the same rate: -5.5% per year.2

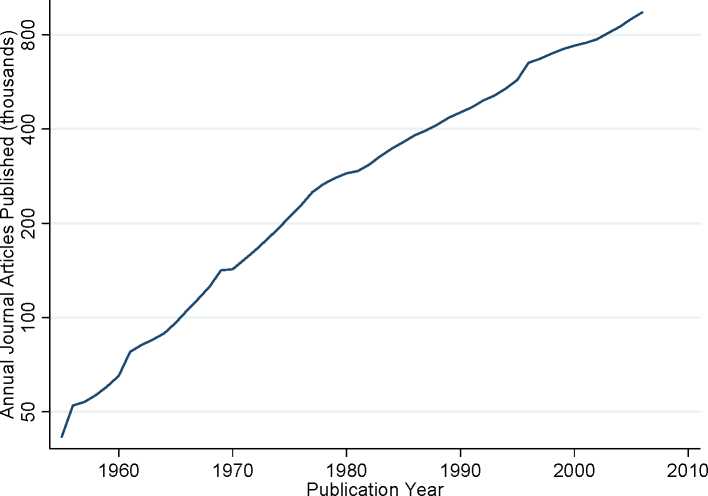

Figure 1: Journal Article Publications per Year, Worldwide

Notes: This figure presents the number of publications in each year, worldwide, as recorded by the Institute of

Scientific Information’s Web of Science database, pooling articles across all fields of science and engineering and

social sciences. Growth rates in publications are similar looking only at authors with U.S. addresses. Over 90% of

the articles are, consistently, in science and engineering fields. See text for further discussion.

Below we will examine richer and more systematic evidence about the implications of

such expansions of knowledge. But it should be clear at this point that innovators face a shifting

landscape in which they become educated and produce new ideas. In fact, one may expect two

natural responses in innovators’ educational decisions as the volume of knowledge expands:

1. First, innovators may spend longer in education;

2. Second, innovators may seek narrower expertise.

2 That is, let N be the total number of papers (or other codified ideas) in the world and let this number grow at rate

gN. Let Q be the fixed number of papers that an individual has time to learn. Then the share of extant knowledge

known by the individual is s = Q/N, and the growth rate of s is then gs = - gN.

More intriguing information

1. A novel selective 11b-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 inhibitor prevents human adipogenesis2. Artificial neural networks as models of stimulus control*

3. The name is absent

4. The Nobel Memorial Prize for Robert F. Engle

5. Income Growth and Mobility of Rural Households in Kenya: Role of Education and Historical Patterns in Poverty Reduction

6. The name is absent

7. Reform of the EU Sugar Regime: Impacts on Sugar Production in Ireland

8. Meat Slaughter and Processing Plants’ Traceability Levels Evidence From Iowa

9. Valuing Access to our Public Lands: A Unique Public Good Pricing Experiment

10. DISCUSSION: ASSESSING STRUCTURAL CHANGE IN THE DEMAND FOR FOOD COMMODITIES