Published in Nunes,T (ed) Special Issue, ‘Giving Meaning to Mathematical Signs: Psychological,

Pedagogical and Cultural Processes‘ Human Development, Vol 52, No 2, April, pp. 129-

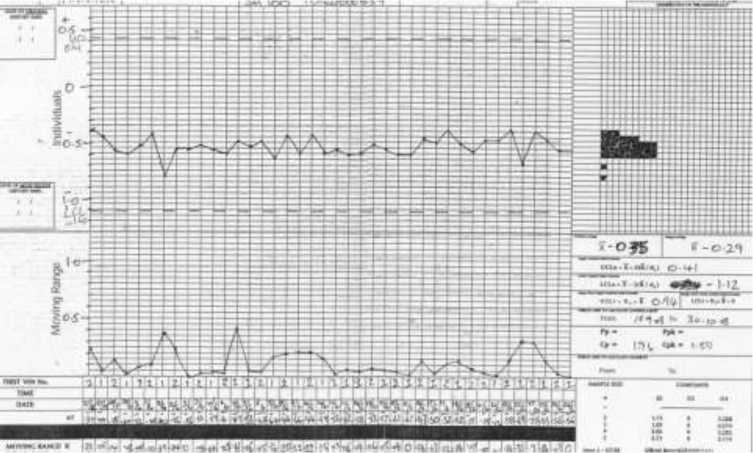

on the chart, and plot the graphical elements by hand: these charts are then handed

over to the process engineers, who undertake a series of complex calculations to

produce measures of efficiency (shown in the bottom right corner of Fig 2), which

become the subject of discussion at team meetings.

Figure 2. An example of an SPC chart, an intended boundary object

Our ethnography derived some understanding of how the charts were used,

what they were intended to do, and the kinds of technomathematical knowledge

necessary for their effective interpretation. In the pedagogic phase of our work we

enhanced the charts electronically: in fact, this became a general methodological

gambit and we coined the term “technologically enhanced boundary object, or TEBO,

to describe the designed artefact. The idea was straightforward: to open up some of

the layers of mathematical structure hidden in the artefact, sometimes by opening

black-boxed calculations to reveal key variables, and in other cases (as in this

example), by outsourcing to our TEBO some of what the employees previously had to

understand.

In the SPC training provided by the factory, we had observed trainees

engaging in physical experiments catalysed by a version of a —shove ha’penny” game

in order to generate sample process data7. By a set of various improvements in

7 Shove ha‘penny is a British game that used to be played in pubs, in which coins are pushed

or flicked up a graduated horizontal board, and bets cast as to where they will land.

11

More intriguing information

1. An Empirical Analysis of the Curvature Factor of the Term Structure of Interest Rates2. The name is absent

3. The name is absent

4. Sectoral specialisation in the EU a macroeconomic perspective

5. The name is absent

6. The Dynamic Cost of the Draft

7. THE USE OF EXTRANEOUS INFORMATION IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF A POLICY SIMULATION MODEL

8. Implementation of a 3GPP LTE Turbo Decoder Accelerator on GPU

9. POWER LAW SIGNATURE IN INDONESIAN LEGISLATIVE ELECTION 1999-2004

10. Nurses' retention and hospital characteristics in New South Wales, CHERE Discussion Paper No 52