Published in Nunes,T (ed) Special Issue, ‘Giving Meaning to Mathematical Signs: Psychological,

Pedagogical and Cultural Processes‘ Human Development, Vol 52, No 2, April, pp. 129-

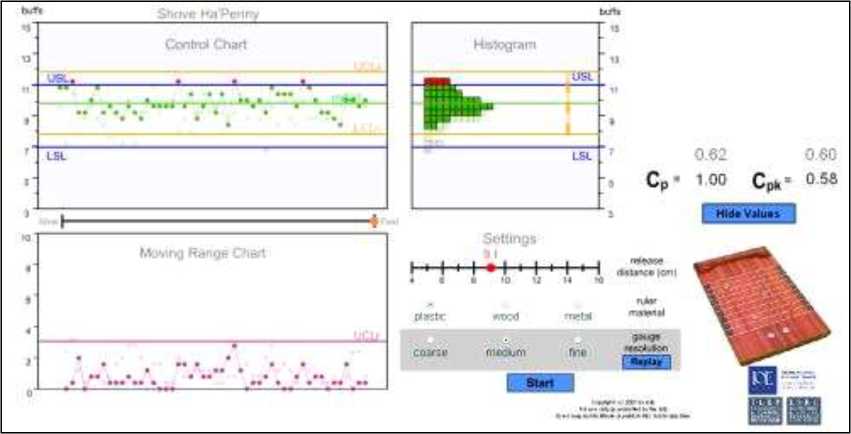

process, such as using a ruler to simulate pushing by hand to systematise

measurement, and plotting the outcome on an SPC chart, the trainees were

encouraged to see how the process could become more tightly controlled

With the TEBO we developed, shown in Figure 3, the employees could

generate trials of 50 ‘flicks‘ in a simulated shove ha‘penny game and the TEBO

plotted where the coin stopped each time on the chart. Employees could therefore

generate large data sets, watch the time series and the histogram of the data grow

simultaneously, and thus observe the key ideas more readily: notice trends over time,

aggregate statistical patterns, see how they emerged from individual trials and how

they were constrained within certain limits in situations of random variation. Our

study indicated that our design was largely successful in enabling the mathematical

underpinnings of the SPC charts to, at least to some extent, be revealed while

maintaining a link with the practice; to ‘reduce the magic‘ as described by one

worker.

Figure 3. The TEBO: automating the processes underlying the construction of an SPC chart

Our research indicates an important, and in the context of this paper, ironic

point about outsourcing (both social and technical) of processing power. The

calculations that powered our TEBO were, of course, outsourced to the machine so

became invisible. Yet for effective communication, we took careful design decisions

so that some of the processes underlying this outsourcing - which parameters were

crucial, how the different representations contributed to the calculated results -

became more visible; and, as we pointed out above, we designed in layers that

12

More intriguing information

1. A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF ALTERNATIVE ECONOMETRIC PACKAGES: AN APPLICATION TO ITALIAN DEPOSIT INTEREST RATES2. The Role of Land Retirement Programs for Management of Water Resources

3. Intertemporal Risk Management Decisions of Farmers under Preference, Market, and Policy Dynamics

4. International Financial Integration*

5. Managing Human Resources in Higher Education: The Implications of a Diversifying Workforce

6. On Evolution of God-Seeking Mind

7. TRADE NEGOTIATIONS AND THE FUTURE OF AMERICAN AGRICULTURE

8. The name is absent

9. Mergers under endogenous minimum quality standard: a note

10. Determinants of U.S. Textile and Apparel Import Trade