Figure 1

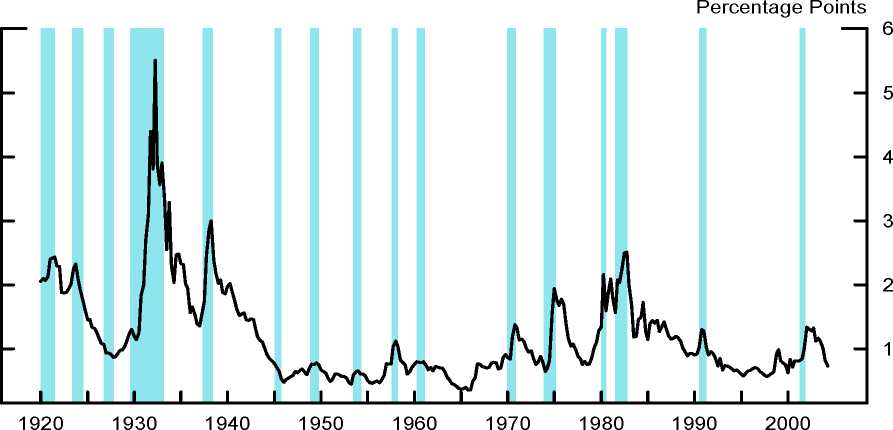

Figure 1: Spread between Baa and Aaa Corporate Yields

Note. Shaded vertical bars denote NBER-dated recessions.

are excessively sensitive to movements in balance sheet variables like cash flow and

net worth.3 These results, although generally consistent with the existence of credit

market imperfections, do not provide direct evidence of the magnitude of agency

costs, leaving the question of the empirical relevance of financial market imperfections

generally unanswered.

In this paper, we use a new firm-level dataset to quantify the magnitude of finan-

cial market fricions. Our panel includes more than 900 large firms over the period

1997Q1 through 2003Q3 and covers a significant portion of the nonfarm nonfinancial

corporate sector. The novel feature of our dataset is that it links balance sheet in-

formation to credit spreads on publicly-traded corporate debt and to market-based

3 This approach has been motivated by the failure of the Q-model of investment to account

adequately for firm-level investment dynamics, a result often attributed to the misspecification

caused by the effects of credit market imperfections. The empirical strategy typically relies on an

a priori chosen proxy for the severity of informational problems in credit markets (e.g., firm size, the

presence of bond rating, etc.) to classify firms into “credit constrained” and “credit unconstrained”

groups. Under the null hypothesis of no credit market frictions, cash flow and other balance sheet

variables should not have a differential effect on investment spending of the two sets of firms; see

Hubbard (1998) for a comprehensive of review of this literature. An alternative interpretation of the

role of cash flow in investment equations that does not rely on credit market frictions is provided by

Kaplan and Zingales (1997) and Cummins, Hassett, and Oliner (1999).

More intriguing information

1. Crime as a Social Cost of Poverty and Inequality: A Review Focusing on Developing Countries2. Migrating Football Players, Transfer Fees and Migration Controls

3. Response speeds of direct and securitized real estate to shocks in the fundamentals

4. Improvements in medical care and technology and reductions in traffic-related fatalities in Great Britain

5. Self-Help Groups and Income Generation in the Informal Settlements of Nairobi

6. The name is absent

7. Trade and Empire, 1700-1870

8. A Dynamic Model of Conflict and Cooperation

9. Wirtschaftslage und Reformprozesse in Estland, Lettland, und Litauen: Bericht 2001

10. IMMIGRATION POLICY AND THE AGRICULTURAL LABOR MARKET: THE EFFECT ON JOB DURATION